This Cop’s Life Unraveled after Tragedy: How His SILENT SUFFERING Came To An End | Adam Meyers

Life is Hard. Business is Challenging. The World is Uncertain.

Leaders, freelancers, and entrepreneurs: Get stories & systems, for navigating the challenges, in your inbox.

It’s time to dive into the brutal truth about what happens when a critical incident shatters a law enforcement officer’s life.

Think police are invincible? Think again. The silent battle Adam Meyers — Stop the Threat, Stop the Stigma — faced after an on-duty shooting in 2016 will help you see the human behind the tragedy. His journey reveals a side of policing—and recovery—you've not seen.

In this, listen-to-learn episode of the Share Life podcast, you’ll discover:

- Why "coping" turned into a terrifying spiral of self-destruction, from alcoholism and drug abuse to casual sex and self-harm.

- The unexpected reason Adam lied to his police chief and deliberately injured himself to avoid work.

- The "rock bottom" moment that involved a social media rant and a beloved pastor.

- How a single, honest decision during a psychological evaluation changed everything.

Are you making the fatal mistake of suffering in silence?

Ready to hear this raw, unfiltered story?

Note: If you’re a first responder struggling, or know someone who is, Adam's story is a powerful reminder: You are not alone, and help is available.

- Watch: Click here to watch this discussion on YouTube directly, or click play on the embedded video above to begin streaming the interview. Click here to subscribe to my YouTube channel.

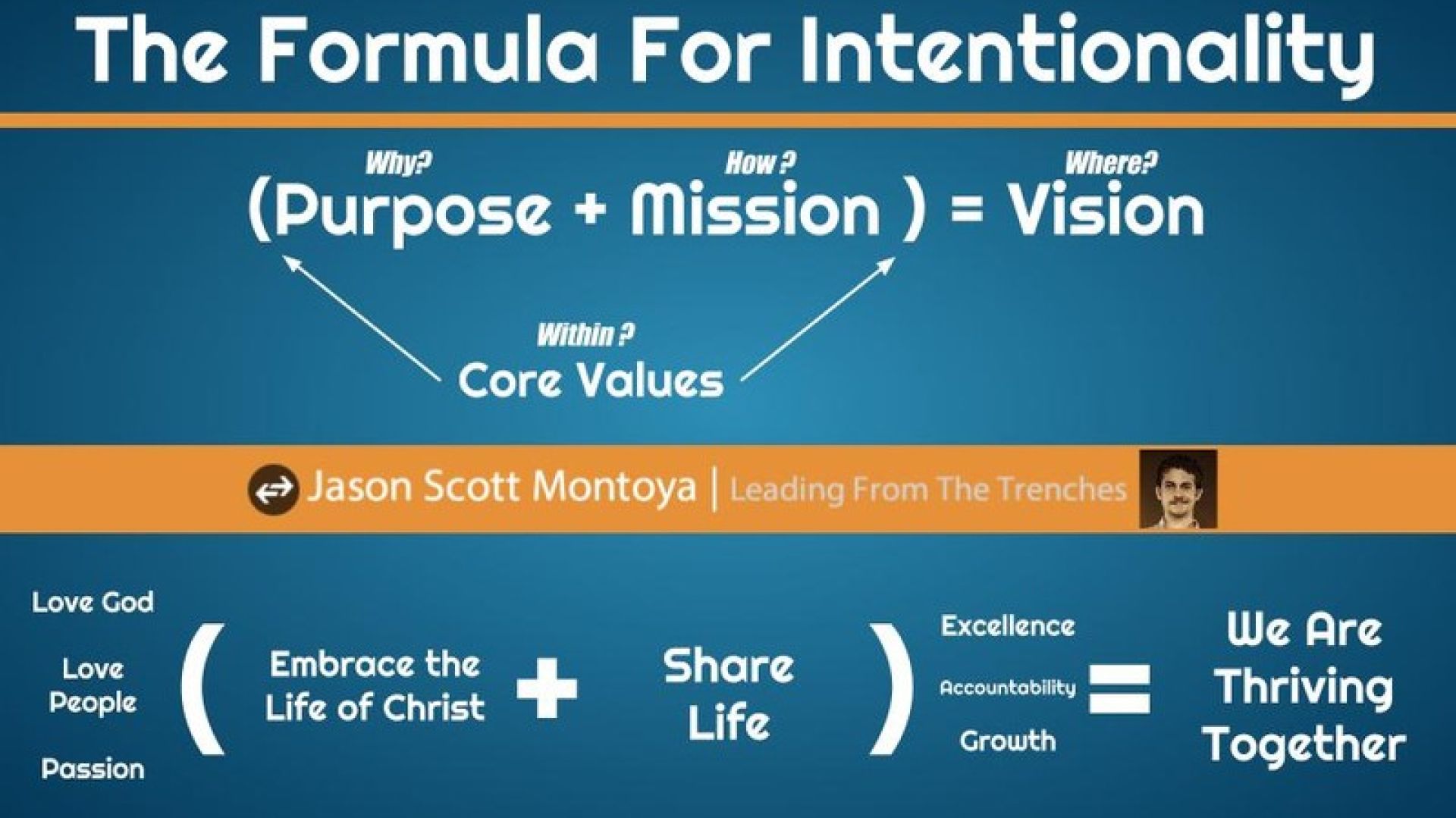

- Listen: Click here to listen in on Spotify directly, or click play below to immediately begin streaming. You can also find this discussion on Pocket Casts, Itunes, Spotify, and wherever you listen to podcasts under the name, Share Life: Systems and Stories to Live Better & Work Smarter or Jason Scott Montoya.

Connect With Adam Meyers

Podcast Episode Transcript

Slightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Adam A. Meyers

(00:00) This is a complete plastic replica of my duty weapon. There are no working parts; it's a Glock Model 22. What I would do is remove the magazine, clear the chamber, and then put it to my temple and pull the trigger. I just wanted to hear that metallic click. I did that easily a dozen times, but I never wanted to die.

Jason Scott Montoya

(00:20) Welcome to a Listen to Learn episode of the Share Life podcast. My name is Jason Scott Montoya, and today I'm speaking with Adam Meyers about the impact of critical incidents on law enforcement officers and their journey toward healing. Thank you so much for joining us, Adam. Say hello to everyone.

Adam A. Meyers

(00:36) Hey everybody, thanks, Jason. I appreciate you giving me this opportunity to share my experience. Hopefully, it'll help somebody.

Jason Scott Montoya

(00:40) Adam A. Myers is a dedicated law enforcement professional with 23 years of experience in Wisconsin, including service as an active-duty United States Army military policeman. Following a critical incident in 2016, Adam bravely navigated years of poor coping and difficult choices. His journey through trauma, mental health challenges, and eventual recovery led him to become a certified peer specialist in Wisconsin. Now a police captain, Adam is committed to sharing his powerful story of resilience and healing to help others recognize the importance of mental health and encourage them to seek support. Adam, go ahead and start with that inciting incident that unraveled your life in many ways. That was April 2016. Take us back to that moment: what happened and what was going on there?

Adam A. Meyers

(01:25) It was Friday, April 8th, 2016, around 5:15 PM. It was a very busy Friday with hundreds of people in a retail store. I was at the police department working on a retail theft report when I was dispatched to our Walmart store. Initially, it wasn't a very urgent call. Dispatch advised me that someone in the store was refusing to leave. This person was with two chaperones who were also struggling with mental health challenges. They were from a state-run mental health facility and were out on a good behavior pass. They went to a restaurant and then to Walmart. When it was time to leave, they refused. Their chaperone called 911.

Initially, the 911 call was a hang-up. Our dispatch center called them back and said, "Hey, we got a 911 call from you guys. If you have an emergency, please call us back," which they did. They kept them on the line so they could update me. It wasn't a very urgent call; we get calls like that all the time at restaurants, retail stores, and houses. I just grabbed my laptop, went out the back of the police department, jumped in my squad car, and started driving to Walmart, which is about two miles away, traveling at a normal rate of speed.

As I was responding, dispatch advised me that this person, Melissa, was walking towards the sporting goods section and trying to take a knife out of the packaging. Eventually, she got the knife, which ended up being a hatchet, not a knife, and started threatening customers and damaging merchandise. When I heard that, it immediately became an urgent call. I turned on my lights and sirens and started responding.

Walmart stores are set up almost the same. There's an auto center in the back of the store, right next to sporting goods. I got on the radio and told other officers I'd be responding through the auto center, thinking I could make contact with her in the sporting goods section and deter her from walking towards the front of the store. However, that changed because dispatch advised me she was threatening customers and walking towards the front.

I entered through the general merchandise entrance. I pulled into the parking lot with lights and sirens, and nobody would get out of the way. I remember people looking at my police car, thinking, "Look, something's going on." I was thinking, "Will you please get out of the way? There's a true emergency in the store. I need to get through." I parked my squad car right by the general merchandise entrance, turned my sirens off, and left my red and blue lights going. I was hoping that since it was Friday and super busy, people would see my police car parked in front of the door and decide not to go through that door.

I exited my patrol vehicle and immediately drew my weapon because I didn't know where she was. She wasn't right inside the vestibule area. I entered the main part of the store and saw a man and a woman. I asked them, "Where is she?" They pointed down towards the Lawn and Garden and Health and Beauty Department, one of the main aisles in Walmart. I ran down there and saw her with her back facing me. I gave her some commands, and she turned around and faced me. That's when I realized she had a hatchet and not a knife. Not that a knife would have been any less threatening, but when they said she was in possession of a knife, I thought it was a pocket knife that a lot of people carry. When I realized it was a hatchet, I continued to give her multiple verbal commands to stop and to drop the hatchet. She wouldn't comply and kept advancing towards me. That's when I shot her. I shot twice. One of my rounds went in and out of her leg, and another round hit her in the sternum area, and she fell to the ground. Unfortunately, many hours later, she died after surgery. I didn't know about that until the following day.

I know when I pulled the trigger, I changed lives. Not only did I take Melissa's life, which is tragic, I changed my life. I changed the lives of the witnesses who saw the shooting, even people on the complete opposite side of the store who heard the gunshots. Everybody there has a story that they were at Walmart, and the police shot somebody. During the investigation, we discovered that Melissa had a six-year-old daughter, which is sad because, at the time, I had young daughters. My daughters are young women now, they're adults, but at the time, that's something I struggled with because I kept thinking, "How would I feel if that happened?" I also understood that Melissa's mom and dad would never see her again. Melissa would never see her family and friends again. It's not something I take very lightly.

After the shooting, I looked at the customers and witnesses and said, "Please check each other and check yourself." I wanted to make sure my bullets didn't hit anyone else, and I wanted to make sure everyone else was okay. A Walmart employee was there; I told them, "Please get on the intercom and ask if there's a nurse or a doctor and please have them come over here and help until the ambulance arrived." The ambulance arrived pretty quickly. Then she was taken to the hospital.

From that point on, my life changed. There's not a day that goes by that I don't think about it. That happened in 2016. It's 2025. It's been nine years, and I still think about it every day.

Jason Scott Montoya

(07:23) If someone hears that story, in terms of process and protocol, did you follow the normal protocol for that type of situation? Help people understand what a police officer should do in that situation compared to what you did.

Adam A. Meyers

(07:46) I did. I followed protocol, policy, and procedure. She had a hatchet, she wasn't listening to me, and she was advancing towards me. I gave her multiple verbal commands to stop and to drop the hatchet. If she had continued walking towards me, she could have caused me great bodily harm or killed me. There were many people in the area. Walmart has many cameras, and we viewed different angles of the shooting. I did what I believe was necessary. I used deadly force not hoping she would die. I never wanted to kill her. I never wanted her to die. That night, after I was cleared from the police department to go home, the first thing I did was walk into my house, kneel next to my loveseat, and pray to God that Melissa wouldn't die.

I didn't go to work that day hoping I would shoot somebody. Is that possible in law enforcement? Sure. But is it probable? Not really. Believe it or not, I think less than 1% of police officers shoot and kill somebody in the line of duty. I did follow all policy and procedure. I was put on administrative leave after the shooting for about 30 days. I was investigated by the district attorney's office, and they cleared me of any wrongdoing. Then I went back to work.

Jason Scott Montoya

(09:15) You mentioned going back home. What were the feelings and emotions you experienced throughout that day, the next day, and in the weeks to follow?

Adam A. Meyers

(09:32) I was a mess. I was in shock. Everything seemed surreal. I was in uniform, and they took my gun when I got back to the police department. Once everything was said and done, they said I could go home. I had to take home police cars, so I walked out the back of the police department, got in my squad car, and drove home. I don't remember driving home. I lived in that community, so I could probably guess the route I took, but it was a blur. The next thing I remember is pulling into my driveway.

After I prayed that Melissa wouldn't die, I remember sitting at the foot of my bed, and I just felt so heavy. It seemed surreal. I knew what I had done, but I just felt alone. At the time, I was divorced. My daughters weren't at my house when I got home, so I went inside, took all my gear off, and then I ordered a pizza and some soda. I turned on the news and tried to see what they were saying about me because the news was at Walmart almost immediately. I felt overwhelmed. I felt very hyper-vigilant too. I remember going to bed, and I slept well that night. I don't know if it was because of an adrenaline dump or all the stress. I was just exhausted.

I slept well, and I remember waking up the next day, thinking, "I have off this weekend. What am I going to do?" I tried to do something normal, something I'd usually do on my days off. I usually get my hair cut, and I usually pick up my kids, so I decided to do that. As I was walking out to my car, I looked at my cell phone, and the chief was calling me. It was a typical conversation: "Hey, how are you doing?" "I'm doing good." He asked, "When can I come and see him?" I said, "Well, I'm going to go get my haircut first and pick up my kids, and then I'll come in and see you." He told me, "Adam, I didn't want to do this over the phone, but Melissa died." I remember sitting there, thinking, "This changes everything." This went from me just shooting somebody to taking their life, killing somebody.

Although I was a military policeman in the army, I didn't go to war. I never shot and killed somebody. I always prided myself throughout my career on never using force. In 23 years of being a cop, I've never even pepper-sprayed anyone. I've never used my baton on anyone. I've used my taser a couple of times, but this whole incident was different. The emotions were all over the place. That's just something I struggled with for many years after: being triggered by certain things and, in the beginning, not knowing what triggered me, what triggered my emotions, what made me crabby. I was 41.

Jason Scott Montoya

(12:30) And how old were you at the time? Do you think that age had any unique intersection with what happened? If it had happened when you were 20 or 30 or even now at 50, do you think it would have been uniquely difficult at that age or time in your life?

Adam A. Meyers

(13:05) I think so because I lived about three and a half, four hours away from my family. We all lived in Wisconsin, but I lived three and a half, four hours away. I was divorced. I had my two daughters half of the week. So that support structure, although it was there, it wasn't physically there. My mom, dad, and sister couldn't come up and just be with me every day to know that I was okay. It was kind of difficult. How do I act around my kids? Because they were still young and impressionable. How do I approach them? How do I tell them what's going on? I think it helped me that I had 13 years in law enforcement by then, so I had a lot of training and experience. I was a firearms instructor.

I don't think the amount of training someone goes through can ever prepare them for something like this because you never truly know how you're going to respond. Someone else could be in the same situation as me and be perfectly fine. Initially, I thought I was perfectly fine. I never thought I'd be suffering the way I did years after because I wanted to go back to work. I had no doubt in my mind I would go back to work. When I was back at work, I was like, "Alright, let's keep going."

Jason Scott Montoya

(14:23) What were the types of thoughts that were coming into your mind those first several weeks? What were you telling yourself, or what was your mind showing you?

Adam A. Meyers

(14:38) When I went back to work after about 30 days, I tried to go back to how I used to be before my shooting, and that was impossible. Slowly but surely, I started suffering and realizing, "Hey, something's not right here." I may not have really identified it or known what I was feeling, but I knew something wasn't right.

I did see a therapist, which I thought was helpful at first. I actually still see a therapist. I was the first officer in the history of the police department to be involved in a shooting. When I was seeing a therapist, I was just seeing a regular therapist. I didn't know that there were therapists specialized in first responders or trauma. So I thought, "Hey, if I just go see a therapist and talk, everything will work itself out and be fine." I remember the first time I went there, the first 45 minutes I was talking, and it felt great. It felt great to get it out. But then when I left, I thought, "You know what? She has no idea what I'm going through. This is a waste of time." So I would go for a couple of weeks and take a month off, then go a couple of months and take the whole summer off, and eventually just stop going altogether, thinking, "Hey, I can take care of this myself. I'm strong. I'm a good cop. I can keep going. As long as I keep going, everything's going to fall into place." I was wrong. One of the best things I could have done was get back into therapy. I thought I could handle it myself, and I was wrong.

Jason Scott Montoya

(16:16) What would you want someone to know if they know an officer going through something like this? What would you want them to know to better understand and respond to that friend, neighbor, or person at church?

Adam A. Meyers

(16:38) We're human, just like anybody else. If you have a friend you care about, sure, they may be a cop, a firefighter, a paramedic, or a nurse. We do have stressful jobs, but we still need the same kind of support, friendship, and love that everybody has. Something as simple as reaching out. If I noticed something was wrong with you, Jason, and we're good friends, and I'm not sure how to approach that, if you can't do it face to face, we have cell phones and technology that works great. I'll send you a text: "Hey Jason, I hope you're doing okay. I love you. I care about you. If you need anything, let me know." Just something as simple as that means a lot. A lot of people did that to me, and I would read my cell phone and think, "Yeah, okay, whatever." But it was still nice to know that somebody out there cared about me. So if you have a first responder in your life and you think they may be struggling, just reach out. Let them know that you're there and willing to help and support them. That means a lot.

Jason Scott Montoya

(17:59) A big part of your spiraling was that you felt like you had to deal with this on your own and suffered in silence. Where did that mindset come from, that you had to be this autonomous person and deal with it yourself? Why didn't you have the natural inclination to be in community?

Adam A. Meyers

(18:13) I'm not sure. I think maybe I just thought I could take care of it myself. Maybe the stigma, maybe worrying about being judged, criticized, suspended, or losing my job. As far back as I can remember, since I was a little boy, I always wanted to be a cop. That's all I ever wanted to do: grow up and be a cop. I lived on Washington Avenue in Racine, and I'd run up to the window every time I'd hear a police car go by, look at my parents, and say, "Hey, an Urkar, an Urkar," because of the siren. I thought he was great. My parents said the first time I saw a police officer get out of the "Urkar," I looked at him and said, "An Urkar man, I want to be an Urkar man." So, all my life, I took steps I thought were necessary to become an "Urkar man," a police officer.

So then when this happens to me, I'm thinking, "This doesn't usually happen to every cop, but I can take care of myself. It'll be fine. I'll just keep going. It'll fall into place." In the early parts of going back to work, there were times that I knew I couldn't go to work, and I would ask, "Hey, I just can't be here today. Can I go home?" And that was fine. After a time, I felt like I had used that all up, and I felt I had to come up with other excuses. I started lying about why I couldn't be at work. One time, I have a 12-inch crescent wrench here, and I hit my knee multiple times to cause enough redness, bruising, and abrasions to go into the emergency room to get checked out. So they'd be like, "Yeah, something's going on here." They did x-rays.

(19:50) They gave me a doctor's excuse and crutches. Then I crutched into my police chief and said, "I can't work." That was during the Fourth of July weekend. I started lying, and I shouldn't have. If I had just been honest and said, even if I didn't understand what was going on, "I can't be here. It's just not safe for me to be here," I believe that would have been okay. But I felt like I couldn't, so I started doing things like self-harm. I started binge eating, and I made myself throw up in the police department so everybody could see me so I would get sent home sick. That's something I'm still shameful of because these people supported me, and my chief at the time supported me too, and I lied to him. I lied to him just because I felt I couldn't be honest and say I couldn't be at work.

Jason Scott Montoya

(20:42) Why did you feel trapped to such a degree that you had to make up these stories with real evidence to support it?

Adam A. Meyers

(20:54) That's a good question. I think part of me just wanted to make sure I didn't have to go to work. There were some times when I went to work that I would go hide. I'd park my squad car behind a building or somewhere I knew nobody would flag me down, and I'd literally pray to God that I wouldn't get a call.

Jason Scott Montoya

(21:14) And what did you do during this time that you were just sitting there?

Adam A. Meyers

(21:16) I'd be on my phone, searching the internet, listening to talk radio. I was dissociating. I remember one time sitting at an intersection in my squad car, and I felt like I was kind of out of my body, looking at my squad car from the outside. I was thinking, "That's... something's not right here." But at the time, I just didn't get it. I didn't understand why it wasn't right, what was going on. Maybe that's why I started calling in sick, because I didn't understand it. Until I could figure it out, I had to make sure that I wasn't at work certain days.

Jason Scott Montoya

(21:54) Do you think in a way that you were trying to avoid that potential situation from happening again?

Adam A. Meyers

(22:00) Absolutely. I was very hyper-vigilant. I was always very tuned into everything. As a police officer, you're always paying attention to your environment, but even more so after my shooting. I remember just looking at every license plate, every car, every street sign, just making sure I always had the edge on anything, just in case something happened. That was a whole different mindset after my shooting.

Jason Scott Montoya

(22:30) Did you get called to any situations with a similar type of situation that you felt a sense of dread having to go to, even if it wasn't the same? Just, "Walmart's calling. I can't go."

Adam A. Meyers

(22:46) Absolutely. Most Walmarts are all set up the same. No matter what Walmart I go into, we have a Walmart in the community where I'm a police officer now; it's all set up the same. Obviously, I'm healthy now; I'm a lot better now. So when I go in, it's not that much of a trigger. It doesn't bother me. But before, it didn't matter what Walmart I went into. The feeling of dread? Absolutely. A year after my shooting, I was promoted to detective. I was the first police department's detective, and I went to multiple critical incidents. So on top of my critical incident and trying to deal with my stuff poorly, I chased a bank robber, went to a crash scene where a guy was huffing and ran over three Girl Scouts and a troop leader and killed them. I was the second officer on scene there. So that cumulative stress on top of what I was trying to work out myself. You know, suicides, suicides with the use of a gun, suicide by hanging. I went to a quadruple homicide where a guy used a shotgun to force entry into a house. So yeah, it was always there. It was always there. I was just trying to maintain it, hold on towards the end of my shift so everything would be okay, and then go on my days off and cope poorly with alcohol, marijuana, casual sex—anything that would kind of make things go away, even if it was momentarily.

Jason Scott Montoya

(24:18) These were poor choices and ways to cope. Did it unfold rapidly, or was it a slow progression over months and years?

Adam A. Meyers

(24:30) It was slow initially. Before my shooting, I collected wine. I had multiple bottles of wine and would have wine every now and then, but I went through those wine bottles like that. Then I went strictly to liquor. I went to liquor because it got me where I wanted to go quicker. It was cheaper. For example, I have a bottle of vodka here, 750 milliliters. I would drink this in 30 minutes or less and just sleep the day away. I would also take Nyquil, cold medicine, sleeping medicine, and make my own cocktails. There was one time I reached into the medicine cabinet and used my daughter's prescribed medicine for her cough; it had codeine in it. It just helped me feel real good. Many times, which I'm shameful to admit, but it's what I did, I would stop at a local gas station and get two or three of these cinnamon whiskey, Fireball Whiskey bottles and drink two or three of them right in my car in the parking lot and either throw them in the back of my car or throw them out the window while I'm driving to wherever I was heading. I would rationalize that it would take me about 30 minutes for the alcohol to kick in. That's not true. That's just the state of mind I was in. I'd figure, "Hey, by the time I get there, then I'll start feeling the effects. Everything would be good." That's just not true. I'm lucky I wasn't arrested or crashed or killed somebody, but I just didn't care. I just didn't care at the time.

Another poor coping strategy was casual sex. I would meet women online, and we'd meet, and sometimes in 30 minutes or less, we'd have sex. To me, sex is special. It's playful, exciting. It's something you share with somebody you love. But I just didn't care. I was looking for the next feel-good, and sex gave that to me. But I remember lying in bed with a woman, thinking, "You know what? You've got to stop this, Adam." I started not liking who I was. The thing is, it caused me more stress, anxiety, and depression than anything else, but not enough for me to stop doing what I was doing, because I was always worried, "What if I get her pregnant? What if I get an STD?" But that still wasn't enough for me not to stop having casual sex.

Jason Scott Montoya

(26:57) Was it simply about the sex, or was there any relational time together?

Adam A. Meyers

(27:23) Sometimes it'd be strictly about the sex. Sometimes we'd hang out for hours and meet again and just kind of hang out and have sex until we don't anymore, and we kind of just go our separate ways.

Jason Scott Montoya

(27:36) And then would it be like a one-time thing, and then you move on to someone else? With several coping mechanisms—alcohol, marijuana, casual sex—were you doing them all to accomplish the same thing, or did they have different approaches for different reasons?

Adam A. Meyers

(27:40) Sometimes. Yes, sometimes. I was doing it to accomplish the same thing. It was an escape for me. The alcohol made me feel good. If I drank too much, I would black out, and then I wouldn't realize what was going on and just kind of sleep the day away. I was a drunk. I drank so much that I don't remember drinking sometimes. I remember when I got new furniture in my living room, the person who delivered my sectional helped me move the old furniture, and there were these little bottles of alcohol underneath, and I was thinking, "Wow, I don't even remember drinking and putting them under there." So even trying marijuana for the first time, it was all just a quick fix to help me escape, to numb my feelings, the thoughts I was having, and to kind of just take a step away from all of that. It did nothing but cause me more stress, anxiety, and depression. It didn't help. It might have helped for a couple of minutes, but I started not to like myself.

Jason Scott Montoya

(28:59) So you became a shell of who you once were, essentially. You don't recognize yourself. And you're wondering how you got here. What's your rock bottom moment?

Adam A. Meyers

(29:20) I'm not sure if I actually had a rock bottom moment. I do remember being at a wedding reception, and I think the wedding reception was around April, close to the anniversary date of my shooting. I remember having a lot of Long Island Iced Teas and then having a pity party for myself. I went into the men's restroom, and I was getting really dizzy. I couldn't really stand up, so I sat down on the toilet, shut the door, and got on social media. I started on my Facebook account and started having a pity party: "I wish I would have called in sick that day. Nobody understands me. Nobody loves me. Nobody gets it." All this stuff.

What upsets me now to say this is my pastor, who has passed away, and my pastor who confirmed me, who I was an acolyte for, he reached out and made a comment on my Facebook page in support of me, something like, "It'll be okay," or whatever, and I told him to "F off." I never got to apologize for that. I don't even remember doing it because I was so intoxicated. But the next day when I read what I had posted, I saw it right there. And I remember my dad even commenting, "I don't think Pastor knows what you mean or what you might be going through, but he's trying to show you support." But I couldn't believe that a man I loved and who was such a role model to me, I told him to "F off" because he was trying to support me. That's pretty rock bottom. I mean, that's pretty bad. What hurts is, he passed away, and I never got to explain myself or apologize. That hurts.

Jason Scott Montoya

(30:57) So how long did this type of behavior go on for, from the moment of the incident to that moment on Facebook?

Adam A. Meyers

(31:18) I would say that would probably be seven or eight years, probably.

Jason Scott Montoya

(31:22) Wow. Okay. And so you had a turning point, a panic attack of sorts. Tell us about that.

Adam A. Meyers

(31:30) I did, on December 28th, 2021. I was at an active shooter training at an elementary school. We were watching PowerPoint presentations about different active shooters in the United States and overseas. I was seated comfortably like I am now, and I started getting really, really hot. I had a knot in my stomach and felt really uncomfortable. About a minute passed, and I reached up to my forehead, and it was drenched in sweat. I was having a panic attack.

Jason Scott Montoya

(31:58) Did you know that at the moment, or is that in retrospect you realized it?

Adam A. Meyers

(32:03) In retrospect, I realized it. However, I knew something wasn't right. So my first instinct was to fight through it and hide that this was happening to me. There were about 20 or 30 other police officers in that room, and they all knew me. They all knew I was in a shooting. They were all from different agencies. If I would have just raised my hand and said, "I can't do this. I need to leave," it would have been okay. They would have understood. But my first knee-jerk reaction was to fight through it and hide that this was happening to me. And I was able to do it.

Then I went on a couple of days off, and then I went back to work. I was working a patrol shift. I was a detective at the time, but I was working a patrol shift because it was New Year's Eve. I got in my squad car at 11:00 AM, and I said, "You know what? Forget it. I'm done. I ain't doing this no more. I quit." I don't think I wanted to quit being a cop. I think I wanted to quit coping the way I had been coping. It wasn't working for me. I think I realized, "Enough's enough, Adam." So I reached out to a sergeant, and a sergeant came and sat in my squad, and I said, "I'm quitting. I need you to come with me to talk to the chief. I'm done. I'm not doing this anymore." And he's like, "Hold up. You're not going to quit. Let's go talk to the chief." The chief and the sergeant were very supportive. They sent me home. The chief told me, "Take some time and reach out when you think you're ready to come back to work."

So I did that. I think maybe about two weeks passed, and I reached out and said, "I'm ready to come back to work." He told me, "In order for you to come back to work, you have to have a fitness for duty test, a psychological evaluation." And I was all for it because I was thinking, "I'm a strong mental health advocate. I've been speaking about my experience. I can take this test. I'm fine. I can go back to work." So I scheduled that appointment. When I was driving to that appointment, I thought to myself, "I'm going to lie. I'm going to try to beat this test," even though it was 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM. I mean, that's a good amount of time. I thought to myself, "I'm going to lie. I'm going to beat this test. I don't need to do this. I'm going to lie." So when I'm sitting in the waiting room, I just thought to myself, "Adam, you have to be honest. You have to be honest. In order for you to get some help, you have to be honest." And that's what I decided to do. I decided to be honest, and I was.

What happened to me is I was unfit for duty after the test. I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder, PTSD, acute stress with dissociative features, and unfit for duty. I couldn't go back to work. I remember looking at that—I have a copy of it right here—and starting to read the results. I started crying because it described me. It described everything I was going through over the years. This was full of answers to questions I had. Now I'm like, "Alright, this is great. Now what do I have to do to get better?" So what I did was I went to the police department and requested a 90-day leave of absence.

(35:06) It was approved. Then I started going to therapy two, three times a week. The police psychologist recommended six months of short-term disability with no guarantee I would go back to work, but to start doing therapy. I was doing that; I wasn't missing any appointments. I felt like I was getting better. Even the psychologist said, "Yeah, you keep doing what you're doing. You could probably be able to go back." It was really helpful. I was really positive in the process, thinking my goal was to go back to work, so I really thought that's what was going to happen.

Jason Scott Montoya

(35:38) What were some of the things you got in that therapy that you were missing, and even the report itself?

Adam A. Meyers

(35:46) I saw the right kind of therapist. I saw a therapist who understood first responders, who understood trauma, who understood PTSD. I did talk therapy. I did something called EMDR, which was very helpful. Biofeedback, which was helpful. I learned more about myself. Then we kind of just went through the assessment and started working on certain things. It's all because I was honest, and that's what was so important. I was put on a safety plan, which I have right here. This is a safety plan because during that assessment, there were some suicidal ideations, and that's okay. I wasn't super excited about it, I'm not going to lie.

Jason Scott Montoya

(36:37) Was it explicit? Like, did you know you were doing that, or was it more in retrospect that's what you were doing?

Adam A. Meyers

(36:42) No, it's... I knew I was doing it. But when I was put on the safety plan, it's different when it's you. For years, I helped people who were struggling with mental health. I was there for people who needed help. Now it was time for me. I needed help. So it's different when you're actually going through something. But I didn't have an issue with it. I knew it was important. I knew why I was on the safety plan.

One of the things I did, I'm going to talk about suicide briefly. That was one of the things in the assessment: there were suicidal ideations. I never truly wanted to die by suicide. What I'm about to explain here, I have no idea why I did it. This is a complete plastic replica of my duty weapon. There are no working parts; it's a Glock Model 22. What I would do is remove the magazine, clear the chamber, take the bullet out, and then put it to my temple and pull the trigger. I just wanted to hear that metallic click. I did that easily a dozen times, but I never wanted to die. I don't understand why I did that. A lot of people tell me, "Maybe you were preparing yourself, maybe deep down somehow you wanted to, and maybe you were trying to build the courage to do it." I don't know. I know there were many times I'd go to bed and ask God not to let me wake up. We had some pretty good conversations, God and me. I wasn't very happy with him, but I'm truly blessed, and I'm still here today. I believe that I'm here with you because God wants me to share my experience. But yeah, I don't know why I did that with my duty weapon.

Jason Scott Montoya

(38:26) Tell us more about your relationship with God and how that played a role in this whole experience.

Adam A. Meyers

(38:32) Sure. I was baptized at a young age, a newborn, born and raised Lutheran. I was confirmed, was an acolyte, went to youth group, went to church every Sunday. When I was a little boy, I don't remember exactly what it was called, but I remember my mom taking me into her room, and there was a little book with all these different colors, and it was the process to welcome God into your heart. I still remember doing that. I think maybe I was five years old; I'm not entirely sure, but I remember that.

The day after my shooting, I wasn't a member of a church where I was a police officer. But my first thought was, "I've got to go talk to a pastor. I have to go to a church. I just don't know what to do, so I'm going to reach out to a pastor, reach out to God, try to find some answers and support." I remember I went to Jacobs Well in Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin. It's a great church. I walked in there, and they were having some kind of special event, and somebody approached me and said, "Can I help you?" I said, "Yeah, can I please speak with a pastor?" And she said, "Well, I think they're all busy right now. Can I help you?" And I said, "Well, I'm a police officer, and I killed somebody yesterday in the line of duty." And she goes, "Well, I think we can find somebody for you." It was great. I sat down with the pastor. I briefly remember our conversation. I don't even remember the pastor's name, but I just felt that's what I needed to do.

Just like the night of my shooting, I prayed to God that Melissa wouldn't die. The next day when I found out she died, I was pretty pissed off at God. I was like, "Come on, I prayed, and now you made me kill somebody?" Like we talked about feelings and emotions, I was all over the place. But even throughout everything I went through, I still continued to pray. I still had hope, even though there were times that I felt hopeless and helpless. I still stuck to my faith and still prayed that I would get through it. Then I came to the realization that this is what God wants me to do. He made me go through hell because he wanted me to be here. He wanted me to be alive. He wanted me to go around and share my journey and let people know that it's okay to talk about your mental health. You're not alone. Don't suffer in silence, and things will be okay. I'm grateful. Even before this podcast, I leaned against the wall and prayed to God, "Please God, let this podcast go well. Please let me reach at least one person." Because that's what it's all about. It's about sharing my experience and helping people.

Jason Scott Montoya

(41:19) So you're getting help, and you're on a temporary six-month plan. How does that play out? What happens at the end of that?

Adam A. Meyers

(41:31) I requested a 90-day leave of absence, and that was granted. At the end of the 90-day leave of absence, I had a meeting with my chief. He told me, "You can either resign, or you're going to be terminated. We're not extending your leave of absence. You can resign, or you're going to be terminated." I thought about it, and then I chose not to resign. This is work-related. Everybody knew I was involved in a shooting. People knew I struggled. There'd be times that a sergeant would show up at my house when I was intoxicated to check on me. He was off duty; I was off duty. People knew. I had worked there for 14 years. I had never been suspended. I had never been disciplined. I received awards and medals. All of a sudden, when I truly needed help, it's like, "You can resign, or you're going to be terminated." So I was terminated.

Jason Scott Montoya

(42:27) You felt a sense of betrayal then, sounds like.

Adam A. Meyers

(42:29) I felt completely abandoned. I know "love" is a strong word, but I loved these guys and gals at the police department. I worked with them for 14 years. We went on very dangerous calls together. They knew me. They knew my family. They knew my daughters. They helped me move. Just like that, it's all over. Since then, I've been completely ghosted. Nobody calls, nobody texts, nobody emails me. On April 28th, a couple of days ago, that was my three-year anniversary of being terminated, and I still don't hear from anybody. That's upsetting. The people I worked with. That really hurts because I think, "Was all that real?" I thought it was real. When I truly needed support, when I truly needed somebody, I felt like I was abandoned. They just kind of washed their hands of me and said, "Adam's not our problem anymore." I remember getting in my Jeep and driving out of the parking lot that day, and I was thinking, "What am I going to do now?" When you talk about suicide, what if I had gone home and killed myself? As far back as I can remember, I wanted to be an "Urkar man." That's all I wanted to do. Now, because of something that happened at work, I did my job, killed somebody in the line of duty, and was struggling. Now I'm terminated.

Jason Scott Montoya

(43:57) Did that set you back? Did you start to regress in any way as a result of that?

Adam A. Meyers

(44:04) I don't think so. I was still depressed. I was thinking of a lot of different things. Driving out of the parking lot, I'm thinking, "What am I going to do now? I've been a cop for 14 years. I don't know anything else but being a police officer. That's all I know." Then I'm thinking, "Nobody's going to hire me. You sit down in an interview and you tell them what happened, they're going to think this guy's a nut. We're not going to hire him." So I'm thinking, "Am I going to go back to college?" My dream job, my life, this was my life. This was my identity. This was everything I knew. I lived, worked, ate, went to training, did everything. For 14 years, I loved being a cop. Then it's over like that, and I'm thinking, "What do I do?" So I went home and started looking for jobs. I was on unemployment because when I went on leave of absence, I didn't receive workers' compensation. I didn't receive short-term disability, nothing like that, which is upsetting because people pay insurance. So when they struggle like this, they have some kind of financial assistance. I feel the reason I didn't was because it wasn't a physical injury. I think if I had broken an arm or a leg, I probably would have gotten paid. I would have healed up and went back to work. So I kept looking for jobs, I was on unemployment, trying to figure out what I'm going to do next.

Jason Scott Montoya

(45:26) How do you keep yourself from becoming jaded and cynical about how it ended with them?

Adam A. Meyers

(45:34) I feel a little jaded. I'm not going to lie. I really do. My daughters still live up near that community, and I visit them, not as much as I want, but I do visit them, and we go grocery shopping and spend time out in the community. I always wonder how it's going to be when I bump into somebody from the police department because it's bound to happen. It's just a matter. I know that if I were to see them first, I would avoid them. But if I had no choice and there's some kind of communication going on, I would probably still shake their hands. "Hey, how are you doing?" I wouldn't go into grave detail as to how my life is or anything like that. I don't hate them. I don't hate anybody at the police department, the current chief, the officers I worked with. I don't. I've just come to realize that this is how it's just supposed to be, and I take that. I just try to use that and share it with other people and hope that it'll start some change.

Jason Scott Montoya

(46:32) How did that play out in terms of your next opportunity, your next vocational step in the police journey?

Adam A. Meyers

(46:43) What happened was, I went home, and my sister Amy, she's one year younger than me, and we've always had a good relationship. Her and I were chatting, and she said, "Why don't you move down here by me?" That's three and a half, four hours away. I'm thinking, and I said, "You know what, Amy, I hardly have any money." And she says, "All you have to do is get down here, and we'll take care of the rest." So that's what I did. I packed my stuff up in my Jeep and drove home to her house. We always joke because I moved in with her and moved into the basement, and we're like, "Hey, you didn't even move into the basement of Mom and Dad's house." At the time, I wasn't seeing a therapist; I wasn't taking medicine. I do take medicine now. I take 20 milligrams of Lexapro every day, and it helps me. But my sister was on the outside looking in. She saw that I was struggling, although I felt that I was okay. So, secretly, behind my back, which I love her for it, she was looking for a therapist for me. She was trying to find a therapist that would be able to help me, and she did. She found one, her name's Sharon. I see her every Monday at 5:00 PM.

What I did was I finally put myself first. As a first responder, we always take care of other people and always put ourselves last. But I needed to put myself first. I needed to get healthy. I needed to get better, and that's what I decided to do. So after getting back into therapy, getting back on medicine, I started feeling a lot better. I thought, "You know what, Adam? I want to be a cop. I still have a desire to be a police officer. I have a lot of training and experience that most police officers don't, especially when it comes to my critical incident." I want to be a police officer. So I started applying. I applied for about 50 police departments in a 30-mile radius of where I was living, and I mailed them out. The next day, police departments started calling, emailing me, scheduling virtual meetings, in-person meetings. I'm like, "Wow, they want me. People are interested in me." I never thought I'd be a captain. Before I started getting healthier, I never knew if I even wanted to after everything I went through. But there was a two-week period where three police departments in three separate counties offered me conditional offers of employment, and I chose the agency I work for now.

I was hired, and shortly after that, I was promoted to captain. My chief now, Chief Sean McGee, supports me 100%. We have a lake patrol. We have a therapy dog. It's a really great police department. It's a smaller police department, but it's great. The support there is awesome. The chief is very supportive. We were out on the boat one time, and he told me, "I know you speak publicly about your mental health. I support you. Keep doing it if you want to, and you can even wear your uniform if you want to do that." Jason, that's one of the reasons why I'm here talking to you: because of that support. That is so important.

Jason Scott Montoya

(49:51) What would you say is the difference between being isolated with a group of people you feel more isolated from versus a community you're more integrated with, where you feel that support and can be your sincere self? How would you contrast your current experience to past experiences?

Adam A. Meyers

(50:11) The community I work for now is great. The community I worked for where my shooting happened was great. When I went back to work, complete strangers came up to me and said they prayed for me. They hoped that I would be okay. They were giving me hugs right on the street, and I was like, "This is great. I don't even know them, and they're caring about me." The community now is wonderful, and the people I work with and the people I work for are wonderful.

I approached the chief in 2023 because I wanted to start a Mental Health Monday campaign in 2024. What we do is the first Monday of every month, we share a story from a member in the community on our Facebook page. It gets published in the newspaper and then on the newspaper's website. A member of the community shares their mental health journey. We've been doing that for about 16 months now, and it's gotten to the point where people are reaching out to us. That's great because we're bridging that gap between the police and those who are struggling with mental health. But it also lets people know that police officers are just like everybody else. We have struggles too. We're not machines. We're not robots. That kind of relationship with the community is great. Policing isn't all about arresting people and writing tickets. It's about working together, progressing together, building something together, and that's what we do. It's a great feeling to know that.

Somebody like me who struggled with mental health and got healthier and got better, lost my job, but then got hired again. That's resilient. That's an example that other people, when they hear my story, have hope: "Hey, I can do that." They get to know me, and they get to know me more as Adam and not a police officer. To work in a community like that is great. You can truly be yourself, and that's okay.

Jason Scott Montoya

(52:11) What would you tell someone who resonates with your story, any particular part of it, along the way towards where you've gotten to at the end, but someone that's before the end at some point from the beginning to the end? What would you want them to know that you wish you knew? What would you want them to have that you wish you had?

Adam A. Meyers

(52:35) I just want them to know that they're not alone, that it's okay to talk about your mental health. You don't have to get on a podcast or on the news or tell everybody your business, but you're not alone. A lot of people are struggling with mental health and suffering in silence. What you're feeling is normal. You may not feel like it's normal because I think a lot of society doesn't normalize it. You're looked at differently if you struggle with mental health. So I think that's why a lot of people keep it inside and don't talk about it. But if you are struggling, please reach out to somebody. As I said earlier, you can send a text message. Even if you don't understand what you're feeling, thinking, or going through, send a text to somebody and say, "I need help. I don't get what's going on, but I know something's not right." That's a step in the right direction. It's not an easy step, but there are so many people out there who are willing to help you, not just because they're paid to do it. Like I said, strangers were coming up to me, saying they prayed for me and they wanted me to be okay. I don't even know them, and they're not getting paid to do that. So, believe it or not, a lot of people struggle with mental health. It doesn't matter what profession you're in, or even if you're unemployed, it's okay to talk about your mental health. It's okay to get help.

Jason Scott Montoya

(53:59) So what do you see as the stigma when you talk about "stop the stigma"?

Adam A. Meyers

(54:05) In first responders, I think the stigma is that image of police officers being strong, invincible. You may see a police officer wearing a tactical vest, with a duty belt with all kinds of stuff, a gun, a taser. To some people, that's very polarizing, intimidating, and people don't understand that we're human, and we have feelings just like everybody else. The stigma associated with mental health gets in the way of people wanting to get help.

With a police officer and other first responders, I truly believe that they're not going to reach out for help unless they absolutely know that they won't be judged, that they won't be suspended, they won't be criticized, they won't lose their livelihood. Like me, at the time I was terminated, 14 years, that's all I knew. We have mortgages, we have families, we have kids, we have boat payments, we have all this stuff. It shouldn't even be in your thought process to reach out and say, "I need help because I'm struggling," but not do it because you might lose your job. But it is. That's why I believe so many first responders die by suicide because they're not willing to risk it. They may do what I did: "I can work this out. If I keep going, it'll fall into place. It'll be okay." But it's okay to ask for help. It's not going to be okay if you're drinking and doing all this other poor coping. It's not going to get better.

Jason Scott Montoya

(55:35) Yeah, taking that first baby step to ask for help and then to receive that help. But what would you say to someone who feels like they've asked for help and they haven't gotten an answer? No one's responded, at least not the people they reached out to.

Adam A. Meyers

(55:58) That's a really good question because when I moved down here, my sister, while she was looking for a therapist, I was making phone calls now and then just to see how long the waiting list would be to see a therapist, and it was five, six months. I'm thinking if somebody is really struggling and they need help now, and they finally have enough courage to reach out and say, "I need help," and they're told, "We can't see you for another six months," that's got to be a huge slap in the face. It's like, "Really? I just finally had enough courage to do it, and now they can't see me." I would say, please don't give up. Please keep reaching out for help. If you have to, go into an emergency room. Walk into an emergency room and say, "I'm struggling, nobody will help me, I need help." Hopefully, you'll get help then. I've heard many stories of people doing that. Don't give up on yourself. You can get better. It can get better. Just don't give up on yourself.

Jason Scott Montoya

(56:58) What else would you want to share that we didn't get a chance to talk about that you wanted an opportunity to talk about?

Adam A. Meyers

(57:05) I just wanted to thank my supporters over the years. I was miserable. I was a crab. I was a horrible person. There are a lot of things that I did that I feel guilty and shameful for. I truly support everybody that was there for me, even the people that I don't know.

Jason Scott Montoya

(57:25) So talk to me about the importance of forgiveness, because I think that's what you're hitting at there: grace and forgiveness.

Adam A. Meyers

(57:29) It's a difficult topic. I know that I did the right thing. I know I did the right thing, and you can't convince me otherwise, but it still doesn't make it easy. Sitting here today, even thinking about it, knowing that I took somebody's life. It's just something I don't take lightly. I truly believe that when I die, I'm going to go to heaven. And I truly believe that when I go to heaven, I'll see Melissa there. I've never shared this with anybody, but I truly believe that. And I truly believe when I'm there, she won't be struggling with mental health. Things will be okay. I do really hope that when I get to see her, she forgives me. I've asked for forgiveness many times. I just feel like it's just something that sits with me. I would love to meet Melissa's mom, dad, and family and ask for forgiveness, to let them know that I'm not a monster. I'm not happy about what I did. I'm not proud about what I did. But it's something that was necessary, and I don't know if they'd ever want to meet me, but I would like that opportunity.

People ask me if I've forgiven myself, and I'm not sure I have. I think I'm trying, but I guess I'm not sure if I have or not. It's something that I am getting better at. I am healthier now, and maybe that will come where I have a breakthrough, and I know. It's just something that sits with me.

Jason Scott Montoya

(59:13) I think another pattern or theme that goes throughout your whole story is the importance of truth: telling yourself the truth, accepting the truth, telling the truth to others. Because when you live a lie, it's only going to get worse. There is no getting better until we start to value truth, right?

Adam A. Meyers

(59:22) Right. There are a lot of people that come up to me and tell me they can't believe that I'm this transparent about my experience, especially because I'm a police captain. "Hey, what if you lose your job?" What I'm doing is more important than my job. Sharing my experience and helping other people is more important than the badge on my chest. Although I truly love being a cop, I really do. If I lose my job, then I lose it, and I'll keep doing what I'm doing now. It's bigger than me. I truly believe God put me on this path. This is what he's wanted me to do all along, even though in the early stages, I didn't want anything to do with him. I was pretty pissed off at him, but I'm very blessed and very grateful for where I am today, and sharing my experience is bigger than me. I know that if I lose my position as a police officer, then so be it.

Jason Scott Montoya

(1:00:29) Tell us how people can connect with you, reach out to you, learn more about your story.

Adam A. Meyers

(1:00:33) You can reach me at stopthethreatstopthestigma.org. If you go there, you'll find my email address and my personal cell phone number. If you call or text, you'll get me. You won't get an answering service. This phone right here will ring. I'll do my best to get back to you and support you. If I can't help you, I'll find resources that can. You can go to the news section and listen to the 911 call. You will hear the gunshots. You will hear me giving verbal commands. I just want to let you know that it could be triggering to you depending on what you've experienced in life, because it's the actual call. Please reach out to me. If you don't feel like you have somebody to reach out to, reach out to me, and I'll do my best to support you and get you the help you need. I've spoken with people all across the world: in the United States, Canada, Germany, Poland, South Africa. I've realized it really doesn't matter where you live in the world; mental health connects us. It doesn't matter where you live or what job you have; we can all relate to it. So if you need somebody to reach out to, I can be that person.

Jason Scott Montoya

(1:01:43) So that's Stop the Threat, StoptheStigma.org. Adam, I appreciate you sharing your story and being vulnerable with us, inspiring and educating those that are listening or watching. My name is Jason Scott Montoya, and this has been an episode of the Share Life Podcast.

Adam A. Meyers

(1:01:48) Thank you, Jason.