Digital Connections, Real Loneliness: Unpacking the New Age of Isolation

Tired of feeling alone in a crowded room?

It's a silent struggle. You're around people, even family or friends, but that deep isolation hits. Why? You think more connections will fix it. You think being busy helps. Think again.

Life is Hard. Business is Challenging. The World is Uncertain.

Leaders, freelancers, and entrepreneurs: Get stories & systems, for navigating the challenges, in your inbox.

We're facing a connection crisis. Loneliness is a public health crisis (comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day). And most advice misses the point.

What if the problem isn't just being alone? What if it's how we're connecting? We're more online than ever, but these digital bonds often lack depth. You might even be trapped by your own internal story.

Curious how our modern world makes loneliness worse? What if your efforts to connect are actually pushing people away? Or what if that person you thought you knew, you absolutely didn't?

Watch the full discussion on the Share Life podcast with Jim Karwisch and Allen Helms, to unmask the hidden costs of our hyper-connected world and discover small steps to make it better.

P.S. If you've ever asked, "What's wrong with me?" when you feel lonely, you're not alone. This Share Life Academy Workshop conversation validates your experience and offers a path forward.

- Watch: Click here to watch this discussion on YouTube directly, or click play on the embedded video above to begin streaming the interview. Click here to subscribe to my YouTube channel.

- Listen: Click here to listen on Spotify directly, or click play below to immediately begin streaming. You can also find this discussion on Pocket Casts, iTunes, Spotify, and wherever you listen to podcasts under the name Share Life: Systems and Stories to Live Better & Work Smarter or Jason Scott Montoya.

Additional Resources

Who is Jim Karwisch?

Jim Karwisch is the founder of Untangled Narrative, where he helps people untangle the stories they live by, enabling them to move forward with clarity, alignment, and momentum. Through his work, Jim guides individuals and communities to rewrite the inner narratives that shape their choices, behaviors, and relationships.

With a background in storytelling, improvisation, coaching, corporate training, and group facilitation, Jim blends structure with spontaneity and logic with intuition. He's known for asking the right question at the right time.

When he's not working with clients or on his upcoming book, Your Untangled Narrative, Jim builds a community of thoughtful changemakers, develops narrative-based tools, and turns lessons from video games and pop culture into surprising insights about real life. He's a sci-fi fan, gamer, podcaster, and highland cow enthusiast who lives near Atlanta, Georgia, with his wife, son, mother-in-law, and a rotating cast of pets.

- You can sign up for his LinkedIn newsletter here.

Who Is Allen Helms?

Alan Helms is an Atlanta-based CRM consultant and the founder of Organic Endeavors. He specializes in helping small companies and startups with their sales and marketing teams, particularly in setting up and optimizing CRM systems like HubSpot and Salesforce. His work involves mapping marketing campaigns into software to collect data, provide insights, and enable better decision-making for company growth and improvement.

What is the Share Life Academy?

The Share Life Academy is a community and place for us to develop ourselves, each other, and our organizations, and to get inspired. It is a place to help us escape survival mode, dream big, see clearly, and achieve great things together. One of our goals is to prioritize the important over the avalanche of urgency, to make sure we keep the ball moving forward on important projects that matter in the long run. It's also a place to discuss the important things that prevent us from finishing them and enable us to succeed.

Fill out the following form to register for this workshop and access the Share Life Academy. You can also click here to learn more.

Historical Event Details

- When was this event? July 16th, 2025, 11am

- Where was this event? Virtual Stream via Riverside to YouTube.

Answered Questions From This Webinar

What is the difference between being lonely and being isolated? Isolation is the physical state of not having people around you. Loneliness is the feeling of being disconnected, which you can experience even when you are in a room full of people you know. (02:34) Is loneliness considered a serious health risk? Yes. Health experts, including the US Surgeon General, have warned that the health risks associated with loneliness are comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day, and they are calling it a "public health crisis." (01:00:07) How does our "inner narrative" affect loneliness? The story you tell yourself about connection is critical. If your inner narrative is that "needing people is a weakness" or "people can't be trusted," you will naturally create distance and protect yourself from connection, leading to feelings of loneliness. (09:29) Why does it seem harder to have deep connections with people now, even people we've known for a long time? In the current social climate, people are more emboldened to share their views, especially online. This can lead to the sudden realization that someone you thought you knew well holds fundamentally different values than you. This sudden re-framing of your relationship can create a profound sense of disconnection, even if you still see them regularly. (15:14) How can modern technology and convenience actually increase loneliness? Technology often removes the organic need for community. When you have two cars, you don't need to ask your neighbor for a ride. When you don't need to rely on others for practical help, the natural, day-to-day interactions that build relationships disappear, and community must then become a more intentional, and therefore more difficult, pursuit. (01:04:31) What is a practical mental framework for dealing with negativity and conflict online? Adopt the principle that "source determines weight." The impact of a comment or opinion should be weighted based on your relationship with and trust in the source. A stranger's angry comment on social media should carry almost zero weight, while the concerns of a trusted friend or family member should carry significant weight. This allows you to filter out noise and invest your emotional energy where it matters. (57:07) What is one of the most powerful things you can do to help someone who is lonely? Intervene in their life and create a safe space for them to be vulnerable. One of the best ways to create that safety is by sharing your own story of struggle first. When you show that you have also been through difficulty, it makes it safe for them to share their own, which is the foundation of a true, healing connection. (01:13:33) If trying to "solve loneliness" feels too overwhelming, what is a better goal? Instead of trying to "solve" loneliness for yourself or someone else, focus on simply "improving the situation." The goal is not to fix everything at once, but to take one small, intentional step. This could be as simple as reaching out to one person you've lost contact with and asking them to get coffee. (01:19:21)

Workshop Transcript

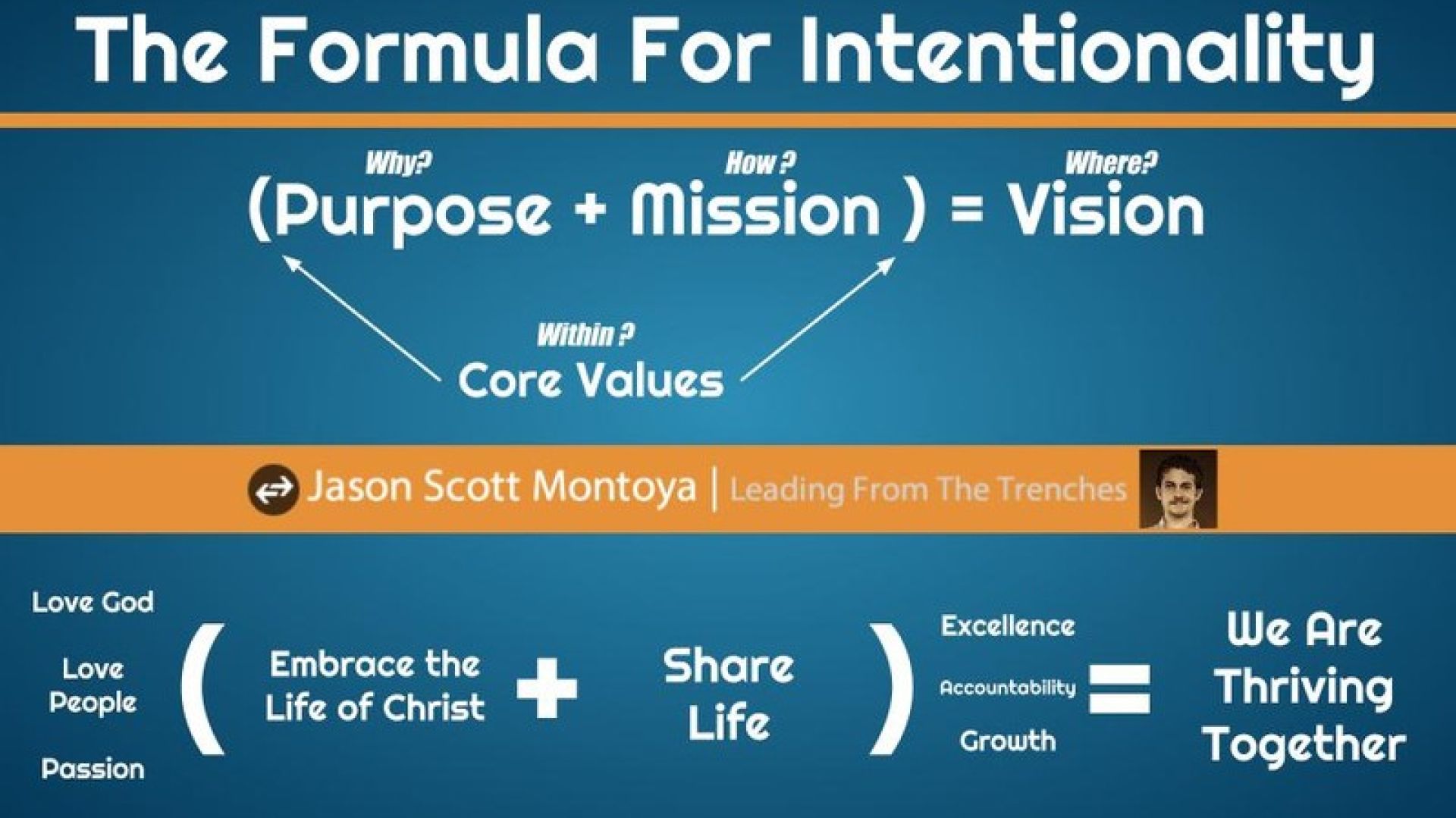

Here's the refined transcript with punctuation, grammar fixes, and redundant parts removed: Jason Montoya (0:00): I moved to Atlanta in 2005. I felt isolated, trapped, and stuck—isolated survivalism, as I describe it. My personal vision statement is "thriving together." That vision for my life, family, and community comes from experiencing the hell of isolated survivalism. There's an interesting connection to social media here. When I was in that deepest, darkest, loneliest place, I was doing some things online and got noticed. Some specific people reached out to me. I was alone, trying to do things, and someone connected with me. The problem was these people were very toxic. But they saw me. I felt seen, acknowledged, and part of something. Because they were toxic, part of me wanted to make them proud or show off for them. That created an orientation in me to create more toxic content because I was trying to do it for these toxic people. Some of the stuff I did, I have regrets and am ashamed that I said and did certain things. Jim Karwisch (1:03): Mm-hmm. Jason Montoya (1:11): When you become vulnerable online, and that vulnerability shows, toxicity can find and capture you. Welcome to a Share Life Academy workshop. Today, we're going to talk about bridging the divide, finding connection in an age of isolation. I'm Jason Scott Montoya, and in this episode, I'm joined by Alan Helms. Alan, say hello. And I'm also joined by Jim Karwisch. Jim, say hello. Jim Karwisch (1:41): Hello everyone. Jason Montoya (1:42): If you don't know Alan, he's a HubSpot and Salesforce CRM Jedi. He's doing the Lord's work, helping companies get out of marketing qualified lead hell—MQL hell, as some might know. Jim is a narrative coach who helps people understand what's holding them back and how to get what they want in life and work. He'll also be leading this workshop about community and isolation. This is the seventh seminar that will conclude this series. Six of those workshops have been with Jim Karwisch leading. This episode will act as a launching pad for Jim Karwisch's new podcast, called Everything is Narrative. I will be joining him for the first episode. Jim's going to take us on a rollercoaster ride through this topic of community and isolation. So, I will let you take it from here, Jim. Jim Karwisch (2:34): The first thing I thought of, if we're talking about isolation and loneliness, is to discuss the difference between those two and set the stage for the different feelings and experiences people are having. If you can figure out where you land, it might be easier to find a starting point to deal with the situation and improve it for yourself or others. Isolation is about not having people around you, not physically being around other people. Loneliness can also mean not having people around, but what's happening now is a deeper loneliness and isolation: being around people—in the same house or job—but feeling the same loneliness as if they weren't there. If you think about Tom Hanks in Castaway, inventing the character of Wilson, he's literally isolated and as lonely as you can be, creating a character to interact with. So, from one end of the spectrum—no one is connecting with me, no one is around—to the other end—someone is in the same room daily, yet I feel disconnected, lonely, and isolated. One more potential is feeling disconnected or isolated from people we can't talk to at a depth we feel safe with. We're polarized, so we don't feel safe discussing certain things, which by itself can feel isolating or lonely. For example, I feel lonely when my wife goes out of town. My son stays with me, so I'm not technically lonely; I can talk to him, and we hang out. But there's a feeling of not having a connection, being isolated from a particular person who is normally very connected with me. So, when she goes away, even if we text or call, that's different from being in the same house but feeling like you can't talk to them about certain things. Where does that land with you guys? Jason Montoya (6:08): I'll throw out a couple of things. One, when you're facing a challenge, difficulty, or suffering, feeling alone can make it feel ten times worse. Our rationality is partially dependent on community, so we lose our minds if we're alone and suffering, feeling forsaken or abandoned. That can be more pronounced when there are literally people around you whom you can't talk to, either because you feel trapped or unsafe. So, there's a shame dynamic there. Another layer is when I had my marketing company; when I shut it down, I went into freelancing. I went from having a business with a team to a business where it's just me. In that transition, I realized I was using the team as a shield, like a safety blanket. It made me feel better. As an independent freelancer, I was facing the world directly. There wasn't any barrier between me and the world. An upset client, a client that didn't pay, or a project that failed—I didn't have a team to absorb that. I had to absorb it directly. I realized in some ways, maybe unhealthy ways, I was avoiding being alone with myself to not have to face those feelings. That transition helped me face and work through those feelings. Those are two things that stick out to me. Jim Karwisch (7:54): Thanks. Jason Montoya (8:04): There are several others, but I'll pause there in case Alan wants to chime in. Alan Helms (8:08): When you're talking, I'm thinking back to the cliché of talking about being lonely versus being alone, which was a lot of what Jim was discussing—isolation versus being lonely. How much of it is a physical situation where you're in the same room or community with people, but you don't feel seen, heard, or able to have a discussion or connection? All the things you just discussed, feeling comfortable and vulnerable enough to have a conversation with someone, or just having the confidence level to bring up certain topics. Versus, and I don't know if it's a choice, some curiosity is around how much of this is a choice that a person makes to say, "I choose to be alone, choose to be by myself for a weekend to recharge" if, for example, I'm an introvert versus an extrovert. How do those factors affect choosing to be alone and isolated versus seeking out community? Jim Karwisch (9:29): Yeah, that's great. That's a natural segue, Alan, into my next point. My work is in narrative. I process everything through narrative. When I think about what Alan just said—how much of it is a choice, how much confidence I have—it leads to: What is your inner narrative? What's the story you are telling yourself about the situation? Narratives protect us, and the depth and strength of that narrative might be out of proportion to the actual risk. We might be able to do something, but we feel unsafe, so we don't move forward. If you go from the extreme of a hermit who lives in a shack or cave and doesn't want anyone else around, they've decided their narrative is that life is about not being around people. You might have the narrative that people are evil, too much trouble, or can't be trusted. Or that needing people is a weakness. Jason Montoya (11:12): And I'll add a personality layer: where we're coming from. I'm highly extroverted, in like the 90th percentile. For me, I'm coming from a place of natural relational community seeking, whereas an introvert may be coming from a different place. So, that transition I went through was difficult because of my personality. Jim Karwisch (11:30): I was talking to my mom just the other day, and I didn't connect it to this topic until you said that. She said, "I was just thinking about it the other day, but I probably would have been just fine if I had just gone and lived in a monastery." She's that type of person. Bless her heart, she had to deal with me. I'm a theater person and an extrovert, so she had to deal with me all those years as I was growing up. She would have been fine if she'd just been alone by everybody. So, I think if you gain energy by being around people, which is how we define extroversion versus introversion, right? How is our internal battery and our connection related to when we are around people, how we connect with those people, how are those people pouring into us, how are we pouring into them, and what's the net effect after we're done being around those people? I gained energy from that situation. I went to a party and came away with a lot more energy that I'll use throughout the week. My girlfriend—I'm not saying my girlfriend, I'm married—but I have this other person in my life who's an introvert. She went to the party with me and needs to rest for two days after having gone to that party. So, the amount of connection that people need of a certain type, I think even introverts have a certain type of connection that they need. They can almost be blindsided by the current climate and how the world behaves and communicates. Introverts can suddenly recognize, "Whoa, it isn't just that I'm fine if I'm not around a lot of people. I'm actually disconnected from a very important person or type of relationship, something I needed, and now that is infringed upon. I don't feel safe in that relationship. I don't feel safe talking to that person." Now, their very small circle was cut off, they feel, and so now they feel worse. You can't really say worse or better, right? We don't know who feels worse, but comparatively, they are feeling worse than they ever had, and they didn't really think it would bother them that badly if they weren't around people. If we jump back to when we were in COVID, at the very beginning, people started processing what it was like not to be around people. Some people thrived; they thought, "This is the best thing ever. Can we just do this for a while?" And we did. Other people were like, "I don't know how to function in this. So much of my world and my ability to be in the world revolves around me connecting with other people, and I'm going to have to learn new skill sets to deal with this." So, when you talked about it being a choice before, Alan, and you talk about them not having enough confidence, do they feel unsafe? Here's one more: if I didn't know someone as well as I thought I did before all the things that have happened in the past, how many years are we going on now where things really have shaken up a lot? Are we on six years now? Jason Montoya (15:12): COVID, we're at five, six years, but I would say the last decade for sure. Jim Karwisch (15:14): Five, six years. Yeah, the last decade. So, when we think about how things are changing and people are becoming more emboldened to say what they think out loud in many different formats and ways, you might suddenly realize that someone you thought you had a deep connection with, and knew well, you absolutely didn't. The level of connection felt good, safe, and rewarding. But as soon as you know that person on a deeper level, suddenly your judgment comes in, their judgment comes in, your misalignment comes in. You feel like you have different values, and suddenly there's a disconnection. Even if you still see that person, you see them in a different light or through a different lens. So now you can feel disconnected from someone when the only thing that really changed is that you recognized you didn't know them like you thought you knew them. For an introvert, if they only have a certain number of people around, and their interactions are very specific—"we see each other on Wednesdays, and we have coffee and talk for hours"—and then suddenly that one thread connecting you to people is severed, what does that do to the person? How are they impacted by that? Any thoughts, Jason or Alan? Jason Montoya (16:42): Yeah. The disconnect between words and actions. If you're connected with someone for a while and they say things, then suddenly they act in a way that seems contradictory to what they said, it's like, "Whoa, what's going on here?" Then it's a matter of, "Well, maybe they're not as sincere, or maybe I misread or misapplied those things." There are a lot of layers that could untangle there. Alan, what do you want to throw out there? Alan Helms (17:28): Yeah, I find it funny. The example Jim brought up is interesting: if you've known someone for a long time and felt close to them, and whether it's COVID or anything else, maybe there's a political conversation, and suddenly you realize you see the world differently than this person, or you assumed they saw it, or maybe they've changed, or maybe you've changed. That can have a big effect on how often you want to hang out with that person and what kind of boundaries you adjust for future interactions. So, I'm curious why that has such a profound effect on a person sometimes when you reach a point of disagreement. There seem to be one of two different approaches you can take: one, you're intrigued, interested, curious why they changed or why you feel differently, and you want to explore that. Versus the other approach: you just shut it off and say, "No, if they don't see things the way I see them or want them to see them, then we can't interact anymore." So, what makes those two situations different? Jason Montoya (19:16): Yeah. I'll give a couple of things I've done that created a really intense reaction. The first thing I did that created a really intense reaction with some friends and family was with my marketing company in 2013. In the Old Testament, there's a passage about the Sabbath year with farmland—every seven years, you're supposed to let the land rest. We decided to take our company through this Sabbath year and apply these principles. That ended up being the last year of the company, a transition year towards shutting it down, which we didn't know when we started. But I had some friends and family who had a very strong reaction to us doing this. They said, "This is an Old Testament thing; this doesn't apply to your business." They had all these reasons, but there was something about how they saw themselves and how they saw the Old Testament and this particular application of it that just kind of really offended them. Or maybe it challenged how they saw things in a way they weren't ready for. I don't know exactly. The other big one was me over the last couple of years getting politically public and active. I'm a Christian and a Republican, and I've been against Trump. I've never gotten on the Trump train, and I've been vocal about the risk and threat he poses to our country, and I voted for a Democrat. So, that also created a very strong reaction with people I know. To your point, Jim, "Wait a second, maybe we don't know each other as well as we thought because you went this way and I went that way." As a Christian, my aim, like Alan said, is to set boundaries but also to keep the tension in place. Jim Karwisch (21:00): You. Jason Montoya (21:10): It's that faith and redemption that even those who have gone a different path can come back. Maybe I've gone off the rails, and I'll come back. Alan Helms (21:17): When you go through situations like that, how do you choose or decide which person you want to continue trying to engage with versus the ones you cast aside and say it's not worth engaging with anymore? Jim Karwisch (21:30): Well, I'm racking my brain for the name of the town in a news story I watched. Everyone worked together, they were neighbors, friendly. If someone was hurting, they all banded together and helped. It was tightly knit, but also very polarized politically. What I found interesting, and this is how I interpreted it, was the expectation. From the time these people in this community were born and raised, into adulthood and making their own choices, they grew up where the person next door was politically different, and they were clear about it. They saw people accepting each other. So, they grew up thinking, "Yes, we are different. And also, if we have trouble, we support each other. If that person needed to get to the hospital, we would immediately help." There's no difference between any of us as far as our community, just because there's a difference in how we view things politically. Alan Helms (22:57): But is that because of how they were raised? Were they given exposure to different ideas? Is it simply a matter of that? Jim Karwisch (23:02): I think it's expectation. I think it's what you feel blindsided by. When you're growing up, if you had giant Komodo lizards wandering around your town, and people fed them apples, then you bring in somebody who has never seen one and they're everywhere. They've been hired as a new teacher and weren't even told there would be Komodo dragons. That person is going to have all these reactions in a way that the people who live there would never understand. People who grew up there from day one will never be able to process that. They were raised in this environment with these expectations and have never been confronted with anything different. If you grew up in a predominantly democratic, Christian, farmer, Dutchman town, and then a Black person moves in, or you move to another community with people of a different shade of brown, or you move closer to the border, and people from different countries share their cultural beliefs with you. If you were never exposed to it, you're assimilating and trying to reconcile all those things in one moment. That's my view: when you recognize, as we were talking about, that somebody you thought you knew for many years, you suddenly find out you don't know them. That whole shift, disorientation, and reframing of how things work happens now. The difference between growing up with that person, recognizing they're the only other kid to play with and very different, and figuring out how to live with each other, is different from thinking they were one person, and suddenly they show you who they were all along. Jason Montoya (25:23): I want to read this. I saw this the other day on marginalrevolution.com. It's a commentary on the situation in India, titled "The Paradox of India." I think it captures what you're describing. In 2004, something extraordinary happened that perfectly captured India's unique nature. A Roman Catholic woman, Sonia Gandhi, voluntarily gave up the prime ministership to a Sikh, Manmohan Singh, in a ceremony presided over by a Muslim president, A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, in a Hindu-majority country, and nobody commented on it. Think about that: in how many countries could this happen without it being the story? In India, the headlines focused on economic policy and coalition politics. The religious identities of the key players were barely mentioned because, well, what would be the point? That is how India works. This wasn't tolerance; it was something deeper. It was the lived experience of a civilization where your accountant might be Jain, your doctor Parsi, your mechanic Muslim, your teacher Christian, and your vegetable vendor Hindu. For festival holidays, everyone got days off for Diwali, Eid, Christmas, Guru Nanak Jayanti, and Good Friday. For secularism isn't the absence of religion, but the presence of all religions. That came to mind as an example of what you're describing. Jim Karwisch (26:37): Absolutely. Imagine being born into that community. When you start asking questions of whoever is raising you—which could be any number of people of different religions and viewpoints—and they say, "Why is that person different?" If everybody's unified answer is, "That's just the way things are. We are all different. We all have varying beliefs, and everyone seems okay with that, so I guess I'm okay with that." You wouldn't be asked in that moment, "Well, that person over there, you may think you know them, but they're likely going to try to kill you at some point." You wouldn't think, "This is horrifying. I might be attacked at any moment." They set the stage for you for the life that you're living. When kids are growing up, the answers they are given to their questions, their curiosity, and how it's handled. If you don't see anything different, and there aren't any different viewpoints, what are you going to ask? What are you going to be curious about? Now we're in a world where, if you just got on your Instagram reel—my cousin sends me 500 Instagram reels daily; that's his love language, and I need to watch all of them. Alan Helms (28:19): His love language is Instagram. Jason Montoya (28:19): [Laughs] Jim Karwisch (28:24): Instagram, yeah. He'll send me things, and I realize he didn't always do that, but the day he started, everything changed about my Instagram because the algorithm picked up what I was watching. Suddenly, the tone of what Instagram thought I would want to see shifted. I was like, "Okay, so now these things he's sending are a part of me, and Instagram sees that as a part of me, and assumes that if I'm opening all of these and watching them, that must be how I view things." Sometimes he sends me things where I'm fine—somebody falls off a horse, gets up, and says, "I'm fine." I'm cool with that. But sometimes I'll just get something where I'm like, "Did that person live through that?" Jason Montoya (29:18): Yeah, did that truck kill him? Jim Karwisch (29:22): "Are they dead now?" The algorithm goes, "Oh, okay, I get it. I know what you like." So, I start getting things in my feed, and I'm like, "Whoa, whoa, whoa. No, this is my boundary. This is the edge to what I know." I don't judge him for having that in his Instagram. I personally would rather not have that question enter my mind: "Did I just watch somebody die?" That's my threshold, and it's different from anyone else around me. Alan, you looked like you were about to say something. Alan Helms (29:58): There are a couple of different directions we could go on that. It's fascinating to me, again, the different tolerance levels people seem to have, whether that's nature or nurture. So, there's that nature-nurture discussion going on, kind of like what we're talking about with being introverted or extroverted. If you're naturally extroverted, you're going to seek out and probably have more touchpoints, more interactions with people. But then you may also feel chemically wired to feel more alone when you don't have anyone in the room. So, how much of it is nature versus nurture? Another obvious rabbit trail we could go down is social media. Does social media amplify our connectedness? Supposedly, some social media creators created it to improve people's connectivity and amplify interactions. But then, at the same time, I think some of us are experiencing more antagonism, and with the algorithms creating certain bubbles around what you're constantly viewing and feeding you more of the same, you can just start going into a different state of mind, which is alarming to some folks. So, there are a couple of things there that I find interesting. Jim Karwisch (31:21): One of the things is the way you go about getting information. Stephen King once talked about writing as a way of transcending time and teleporting thoughts, basically being telepathic. He wrote in one of his books, "I'm talking into your mind right now." I think it's in his book On Writing. He's like, "I'm typing into your—you are reading these words that I typed at a different time. I may have never met you, and yet I'm sharing these thoughts." Now, you've got this telepathy where anyone at any point can share anything they're thinking, whether they've thought it through well or not. They can share anything they've received from someone else, and it doesn't matter how much they've really thought through or even digested what they received. Sometimes I'll get things forwarded to me that the person didn't even read, and that makes me go, "Wait." Jason Montoya (32:44): Yeah. Jim Karwisch (32:49): "Did you mean to send this to me? This is pretty crazy stuff." And they're like, "I didn't even read it. It's by this author, and I know you like them." And I'm like, "Okay, don't do that, because I was totally prepared for this context, and you just sent me something, and this is not at all what I would expect to see from you because I would expect that it would reach your threshold." Well, it didn't because I didn't read it; I just forwarded it. Jason Montoya (32:58): Well, I... Yeah. I think of Twitter specifically, you could probably apply this across social media to Twitter X. As like our societal brain, just thinking out loud; it's what's going on in our head, and now it's just being made visible when it wasn't quite so visible before. I think, too, my experiences about doing these things that had visceral reactions in my own life—there's something about social media where you do get in terms of the algorithm; it can shape around what you want to see. But then if you are connected with people who are different, you're also going to see what they see and how they see the world, and so you're going to be exposed to that. And you're going to have that reaction, we're all going to have that reaction, right? I'm going to have that reaction to somebody that I think is way off the grid, morally or whatever, and I'm going to see that, and maybe it was already there before, but now I see it. So the act of seeing makes us aware of things to a level that if you don't have a framework to prioritize and do something with it—kind of like what you said, Jim, "I don't want to see if this person died or not"—if you don't have a way to handle that, then it can lead you to some dark places. Jim Karwisch (34:37): Yeah, absolutely. Alan Helms (34:41): So, how would you control that in social media? You don't control the algorithm. I guess you could, if you had a lot of time and intention, try to train your algorithm by only clicking on things you want to see. But I think we've all experienced doing a specific Google search that somehow gets handed off to Facebook, and suddenly you start getting served Ford ads over and over again in your feed because you were looking at buying a new Ford truck. The algorithm obviously has its own desires and purpose. And you have the same thing with just a state of mind. If your friends are interested in a certain thing, you're probably going to be fed that. So, I mean, you could go out and befriend or unfriend all the people you grew up with and then try to alter your friendship group. But the question is, I don't feel like you have as much control over the algorithm and what you interact with. Jim Karwisch (36:16): Well, I haven't... Jason Montoya (36:16): I was going to say, I think it depends. Jim Karwisch (36:17): Go ahead, Jason. Jason Montoya (36:17): I think something like Twitter X, Blue Sky, Threads—those are more topical. You tend to connect with people who have some shared topical interest. Whereas Facebook, at least historically, has been more, or even LinkedIn, like people you've connected with probably in real life, and now you're there. So, my neighbor might have a completely different religion or political view, but we're literally next to each other. So, I think connecting with them on Facebook, we may not see things the same way, but we're neighbors. That creates an interesting overlay. Whereas on Twitter, Jim and I met on Twitter before we met in real life, and it was a shared topic—it happened to be an Andy Stanley sermon. So, I think you can shape, if you're shaping your algorithm on social media where it's interesting, I think you have more control over it. But for me, I use Feedly. I just have my own feed. I put all the things I want in my feed into there, and then I use Feedly, and I don't rely as much on the social media feeds. Although I think YouTube's algorithm is a lot better because YouTube, at least the long-form content, tends to be a more fruitful type of content. Whereas social media can be very instant. You watch like a second, a few seconds. So, it's more like it's going to be stuff that's kind of more junk food. So, I think the YouTube algorithm is better because the content is better, but you could still end up in some junky places on YouTube too. But I think the feed is going to reveal some stuff about ourselves that we may not like, and so we may have to set boundaries around what we use and how we use it. Jim Karwisch (38:10): There are a couple of different metaphors I use when talking about this, and it takes social media and puts it back into the physical world. It's not a perfect analogy, but I think it serves the purpose. Imagine you lived and worked in the same town, and everyone worked for a particular factory. That's what the whole town is centered around. There are a few people who work elsewhere, like a grocery store, but over 90% of the people work at this factory, pretty much the same hours. There are only so many places to go on break or at lunch. So, when you leave work for a little while and go to eat, the people around you will be talking about whatever they're talking about. You'll be there, hearing what they have to say. Your ability to process the wild things they're saying will depend on many factors. A big one is that this person tends to talk that way about these types of things, and if you're going to be around them, you'll probably hear those things. If you want to do something about it, you could try to impose your will and say, "I want you to stop talking about that in public because that makes a lot of us uncomfortable." You could do something about it. But what happens in most situations is, "That's so-and-so; he just is that way." When somebody starts acting wild and crazy, somebody new moves to town and says, "Is that guy insane?" And they're like, "That's Joe. Joe's harmless." "Joe seems like he's not harmless. Is Joe crazy?" And they're like, "Don't worry about Joe. Joe's here. Joe does a good job at the factory. He goes to church every Sunday. Don't worry about Joe." So, when you look at your social media, you have the ability to engage with it or not. That's one choice. Another is that I have the ability to set my mind in a particular place when I go into social media to prepare for it. I know when I go to Instagram, I'm probably going to see a few things that I may not want to see, and then I have to thumb it down or whatever. But if you go in unprepared to experience a lot of these things, and you're not clear on your own values, you're not prepared for the fact that people are going to have wildly different opinions, or you're somebody who's so wound up on a particular issue that if anybody says anything different, you're going to get viscerally upset. If any of those things are true, you're not prepared to go into it. You're not intentional about your thoughts when you go into it. You're just not ready. Then you're probably going to get hit with things differently than, "You know what? It's time for lunch. I'm going to go in and sit down, and Joe's probably going to say a lot of wild stuff." The second thing is that I have different levels of intentionality and different reasons for different social media. So, Instagram I handle differently than TikTok or Facebook. When I go on Facebook, I know what I'm going to see because the people I've friended there are literally the people I know. It's not tailored. If I know you and we're friends, then you're my Facebook friend. That means that when I go there, and if you have a really strong political message and it's different from mine, I'm probably going to hear it there. When I go to Instagram, it's different. When I go to TikTok, it's different. So, when I go in, I'm like, "Okay, I'm going to go check Facebook." The amount of time I spend on Facebook and how I engage with it is different than how much time I would spend on any of the other social media because I know that I'm walking into uncharted territory of what might have happened that day in the news and what people might be saying about it. So, I'll throw it back to you guys for thoughts. Jason Montoya (43:00): Yeah, Alan, I'd be curious, what do you see as the connection between social media and loneliness, or lack of community? Alan Helms (43:12): One thing is, I think we may want to talk about what the problem of loneliness is. Are we trying to attack that as a universal problem, or is it only a problem when someone gets so lonely that they do something horrible and end up on CNN? Or is it just a depression-type thing? So, that's one part of it I'd like to circle back around to. But in answering your question, social media seems to me to be amplifying; it's a new way of communication. I think it has, and to Jim's point, it's probably different on all the different levels, right? If I'm talking to my teenage niece, there are certain social media platforms she wants to use, and she uses them for different reasons that would not even occur to me. Sharing outfits with her girlfriends, for example. So, maybe that's just a way they communicate, or they have a different messaging app they prefer. I think part of it is just a different channel. Where we used to communicate by voice versus sign language versus face-to-face versus over the phone. So, fundamentally, it's just a platform of communication. But then, each platform has its pros and cons. If you're face-to-face, you can see body language, read facial cues, and judge the context of the environment. As Jim was talking about, you're at a familiar lunch counter, surrounded by people you know, it's a whole different conversation versus just typing something out on your computer. There's a buffer or perceived buffer in what you're saying. And obviously, the challenge society has is people are emboldened or don't think through what they're posting and just fire off a very dangerous, slanderous, or regrettable comment that they might wish they hadn't sent or would have softened in a different channel. So, I think that's part of it. If I just circle back around, it's amplifying. People who probably weren't communicating in the past are now communicating. So, people who were stuck living alone in their own bubble are now given a platform where they can communicate, and you can start seeing different signals, different mental illnesses coming out that you wouldn't have realized before because it took a phone call to seek a one-to-one conversation. Now you have a broadcast type of conversation, and it can be expanded. So, there's a lot going on. Jim Karwisch (46:50): Mm-hmm. Jason Montoya (46:58): I'll throw a couple of things in there. On the communication piece and the internet as a whole, social media is part of that. Messaging is part of that. If you remember the Transformers movies, the character of Bumblebee had no ability to speak. His voice box was broken, so he used the radio, scanning through and pulling what people were saying to communicate what he needed. You'd hear him say three words from this guy, three words from a song, two words from a sportscaster. I think that's how I think about memes, particularly—they give you a way to say something, to communicate something. Maybe you don't have that ability, but it gives you a voice when you didn't have it, which can be good and bad. But it can also be fun and exciting when you have friends with animated GIFs and memes. It also creates shared languages, a whole new cultural layer that's easier to integrate the younger you are when exposed to it. The other thing I would say is, I moved in 2005 and ended up in a chaotic place of loneliness—trapped, stuck, isolated. I describe it as isolated survivalism. I've written a personal vision statement, "thriving together," which is the vision I have for my life, family, and community; it levels up. A lot of it comes out of that experience of facing the hell, the misery of isolated survivalism. There's an interesting connection to social media I want to make: when I was in that deepest, darkest, loneliest place, I was doing some things online and got noticed. Some specific people noticed me and reached out. So, I was alone, trying to do some stuff, and I got someone that connected. The problem was, these people were very toxic. But they saw me. I felt seen, acknowledged, and part of something. Because they were toxic, part of me wanted to make them proud or show off for them. That created an orientation in me to create more toxic content because I was trying to do it for this toxic person. That was kind of pre-social media, so I'm glad there wasn't as much as there is now, because some of the stuff I did, I have regrets, and I'm ashamed that I said and did certain things. This person was in California; if the internet wasn't around, this person would have never found me, and I would have probably been safer, having worked through my issues in a smaller environment. Part of the dynamic is when you become vulnerable online, and that vulnerability shows, then toxicity can find and capture you. Jim Karwisch (50:44): One more thing is the pace and lack of barrier to entry for sharing thoughts. I've noticed friends who speak differently when they're really upset than when they're calmed down. I know that about them. Alan Helms (51:04): Absolutely. Jim Karwisch (51:05): When they start talking, I'm like, "You probably just want to wait. Give yourself 10 minutes, and then talk, because right now that's crazy talk." But now, take that same person, not overly emotional, but go out for drinks, and the same problem happens. They have a few drinks and start talking in a way that doesn't represent their values. The idea that going out for drinks with this person means you might experience them saying something they don't really mean, or they do mean it but not to the emotional level they're sharing it. You understand them and what they would actually do, how they would act in a real situation. But they get into another situation where they're emotional or have had a few drinks, and they talk like they would do something different. Now, take that type of talk and give people the ability to say it instantaneously, with no one to say, "Hey, not right now." They can say as much as they want, as quickly as they want, and nothing is blocking it. Alan Helms (52:29): I think the biggest thing there is it's a difference between a one-to-one conversation. If you're out having drinks and talking with someone, or having a one-to-one conversation and someone gets heated, it's all based on your one-to-one relationship. But most of these social media platforms are public; it's a broadcast. It's a one-to-many conversation, and you're putting a lot of information out there across different audiences. So, 20% of your friend group might agree, 20% violently disagree, there's a group in the middle, there's family, friends, coworkers. And you're having a one-to-one conversation that everyone's part of, and you may not want everyone to be part of that. It's so easy; the barrier to entry to simply post something on Facebook or Instagram is just typing it out and hitting send. It's about knowing what kind of channels. I've tried to consider: is this going to everybody? Am I clear that this is going to everybody versus when do I take this offline and just have this conversation one-to-one? Trying to learn those different types of techniques while on social media. Jim Karwisch (54:02): Well, let's take it away from social media for a second. Let's do a different take on it. Back when we were really newspaper-heavy, before social media, someone could pay a lot of money and take out a full-page ad in a major newspaper to state their belief. Certain things would happen; people would talk about it. In fact, it would be in the next newspaper that people were talking about the previous edition because something would have affected society. But when someone went to the trouble—spent the money, made the phone call, filled out the form, got it in by a certain time—it stated something different about their intention. The person who received it probably was like, "Are you sure you want to say that? This is wild, right?" Or there was an editor who was like, "Well, we don't let people put that kind of thing in the newspaper." There were certain things that might be in the way. So, somebody got all the way to the place where that thing was in the newspaper. They had plenty of time to calm down, plenty of time to think through it, and it still was in the newspaper. So, it was taken with a different weight. Now, if someone is taking the weight of reading something on the Internet as if that person had full intentionality behind it, thought it through, spent money to do it, and it had gone through other people to look at it and make sure it was okay, and then you saw it—that'd be very different. But I think people do feel as though they are personally attacked by that thing that that person said, in a format and in a way that was too easy for them to do. So, a lot of times, when I read things that would normally make me angry if they were said to me one-on-one, but I read it, and I go, "Okay, well, this is rage baiting." Or I read it, and I go, "Bless their heart, that person is probably intoxicated right now and is just going to town on social media." I'm going to take this with less weight. I'm not as upset because their words don't have as much weight to them. Other people, everything's the same to them, and it's all like they're being talked to by one person face-to-face. You can tell when they read it, they are instantly red-faced, their heart's pumping, their adrenaline's going, and they're yelling back at that person, "How dare you say something like that? Or how dare you put this out there for everybody to see?" So, I think our preparedness and our context—it's confusing. It's confusing all the time. You have to really get your bearings if you're going to gauge what type of reaction you should be having to this. My wife is very susceptible to it, and she will have big reactions sometimes, and I'm like, "Honey, that's the reaction they want you to have. That's rage baiting. They wanted you to be upset, and if you do something back, that's actually part of the game. That's part of their plan." I'm sorry, Jason. Go ahead. Jason Montoya (57:07): Yeah, knowing the game you're playing and your goal, and then figuring out how to move towards that goal, I think, is the higher level. But the source and weight thing is really helpful. Andy Stanley, in one of his sermons, talks about how source determines weight. So your father saying something is different than a stranger at Starbucks, just due to the nature of the relationship. Sometimes it should be the opposite because of the topic. The weight determines impact, and then impact determines outcome. So, having a weighting framework is super important. The way I think about it is, if you're going to continually engage with me in bad faith, then I'm going to take that weight. Maybe I have a default weight, like I'll give you the benefit of the doubt, and then you earn trust or lose trust. If you lose all your trust, then I'm giving you zero weight. I'll always leave a door open if you want to come back into the fold, but I'm going to focus on people who have higher weight for the most part. That's kind of where I've been shifting. Historically, I would give people more weight than I should have out of optimism—a false optimism, meaning I didn't want to see them for who they really were. I had to see them as, "Okay, this person is just toxic or terrible or whatever, or just isn't interested, or maybe they have another agenda, and I'm not even reading what that is." So, I would just keep giving them more weight than I should have. Now I've been practicing taking that weight to the bottom and then interacting with them as if they have that amount of weight. It can go the other way too, where you don't give someone weight that you should. You've given them zero weight when maybe you should listen to them. That would be like a teenage boy not listening to his parents in an extreme example, but it could be an adult too, not listening to their spouse or whatever. Alan, what do you think? Alan Helms (59:20): A lot of the conversation is about communication styles. To circle back to the original conversation, what does that have to do with loneliness versus being alone? And is that really, who's having the problem with this? Do we see that as a universal challenge? Is the idea that we see this as an epidemic of sorts of loneliness? Is that what we're seeing as the problem, or is it just a simple matter that we're trying to grow into different types of communication styles and having to learn different skills? Jim Karwisch (1:00:07): To answer part of that, part of what came up when we were planning for this talk is that it's being called a public health crisis in the U.S. Experts, including the U.S. Surgeon General and World Health Organizations, warn that loneliness carries health risks comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day. So, they're calling this a public health crisis of loneliness. These are people who are worried about the health of people overall. As things are shifting and changing, the conversation could be a one-on-one: "Alan, how are you doing? Are you feeling lonely?" And then we could look at it from our own community: "How are the people in our community doing?" But now it's like, "How is the world doing?" And if you're not talking just about the things that got brought up earlier, like recognizing somebody's mental health that you didn't realize before because of how they're communicating, recognizing somebody's political leanings, recognizing their values are different than yours—all those types of things. Because we are moving further and further away from needing to be physically around each other, we're increasing the ability to communicate with each other with very little intentionality necessary. We've shaped an environment where you can feel attacked, unsafe, all sorts of things, to a point where you can feel alone when you're surrounded by people. You can feel disconnected when everyone's around you because what's running the show underneath the operating system in your mind is now all scrambled up, and your narrative is different than it used to be. You don't feel like that person is valuable enough for you to share with them. You don't feel like you can trust them. The same person, different context, different level or depth of knowledge of them—those types of things. So, I think that things are changing so rapidly. Communication is happening so fast, and we are physically more and more distant from one another than we have been in the past. People's mental operating systems are not upgraded to be able to deal with that. Combine that with COVID, combine that with the political landscape, and things people are feeling safer and safer to talk about more and more boldly. I think more and more people are feeling less and less safe or less and less loving or caring about other people. They're feeling more and more jaded. They're feeling more and more judgmental. They're more and more polarized, cutting people out of their life. The number of times I see people who are just like, "Yeah, I had to cut out like 10 people out of my life because of what they said about this one post." And it's like, "Okay, do you mean like people that you kind of know, or did you cut out deeply rooted, relationally complex members of your community because of one thing they said?" I think our ability to handle the current situation and the current world—some of us are doing a little bit better at it than others, but I don't know that we're catching up as fast as we need to be or as would make the world able to be processed. Not 100%. We've got to level up to be able to handle a lot of what's going on. Jason Montoya (1:03:44): We're having to level up quickly. So, in regards to the loneliness epidemic, here are some stats based on a survey. 73% of people think the loneliness pandemic is caused by technology as a contributor, which is why I think we keep talking about it. 66% say insufficient time with family. 62% say people are overworked, too busy, or tired. 60% say mental health challenges harm relationships with others. 58% say living in a society that's too individualistic. And then no religious or spiritual life, too much focus on one's own feelings, and the changing nature of work with more remote and hybrid schedules were perceived causes of loneliness by around 50% of people. So that's an interesting couple of layers. Technology reveals things. I'll give you just a practical example. We had one car, I think this was last year or a year ago, and I needed to get somewhere, but my wife was using the car. So, I asked my neighbor to give me a ride, which he did happily. Now, we had a car ride together. We're having a social interaction, community. The technology of having two cars, which is a fairly cultural thing in a family, makes it so you don't need your neighbors as much. But because we had one car, I needed my neighbor. By needing other people, you see them more and interact with them more. When you have needs, and you help them, and they help you, you build that relationship naturally, organically. I think a lot of what's happening with technology is it's removing those organic levers and triggers for community, making us do those things intentionally versus just it happening organically. Does that make sense? Jim Karwisch (1:05:42): Yeah. Imagine that you lived at a level of need where you counted on the people immediately surrounding you in the community for certain things. If they didn't hold up their part, we starve, or we freeze to death, or our children don't learn—all sorts of different things. Jason Montoya (1:05:59): Which gives us purpose too. If people don't need what you have to offer, then what purpose do you serve? Jim Karwisch (1:06:13): Yeah, but it also gives context and weight. It helps us weigh some of the things we were talking about earlier. If somebody says something to me that I find to be wild, but it's the same person who pulled me out of the river when I was drowning—that person got out of their car, saw me, grabbed my arm, pulled me out, we exchanged information, I thanked them so much, offered to buy them lunch. That person saved my life. Then later, I found out they have some pretty intense beliefs about some things. In one case, I know exactly what that person would do if I was drowning. In the other case, I know they have some beliefs. Where does that put me as far as how much I'm willing to be curious about why they believe what they believe, or to know more about how deeply they believe what they believe? Are they parroting something else they've heard? How much do I weigh this, and how curious am I about going further into this? If you remove all that need, and all of us are pretty much fine just having DoorDash and living inside our own homes with no need for anybody else except the DoorDash person, then what balances out any of the things that we hear or see that are coming at us through the technology we were talking about a minute ago? Jason Montoya (1:07:37): And one thing I'll add quickly is we can trust people for different things, and it doesn't have to be a blanket thing. For example, I may not trust Jim to fly an airplane. But I might trust him when it comes to coaching someone. So, I think we can be more complex-sensitive to our trust. You may trust someone to fix your car but not to watch your kid. We can be more selective in certain ways. Jim Karwisch (1:07:52): You should not. Yeah, and the level of depth of knowledge about a person, really knowing somebody, versus just being exposed to them in a particular way. When I've sat down and had deep conversations with people in my past and we discovered something fundamentally different about us, many of those situations led to ongoing conversations about those things while being friends and supporting each other as far as community went. We would discover, "Wait a minute, we have values that seem off from each other." But instead of saying we're just not going to be around each other, it caused us to lean in. "I want to understand more. Tell me more stories. Tell me more about how you grew up. What caused you to think this? I want to understand you at a deep enough level that this makes sense to me from what I'm experiencing of you as a person and what you say you believe, because this doesn't seem like it can resolve. It doesn't seem like this all comes down to one person." Does it make me lean in? Does it make me lean back? Does it make me want to cut it off? If we don't need each other, and we're not around each other, and we're hearing things that are unfiltered and coming at us all the time, it makes a lot of sense that we would go, "Nope, nope, nope." And that would be all sorts of opportunities that we wouldn't ever get or take because of how the situation was presented to us. Jason Montoya (1:09:57): Alan, start pulling us in here and packaging us into something to take away? Alan Helms (1:10:00): I don't know if I'm qualified to do that. It's an interesting conversation. I thought it was fascinating that we were talking about really just different conversational and communication styles at the end of the day when the original conversation was supposedly about loneliness. Jim Karwisch (1:10:20): Let me interject this, and you keep going, but I would almost say that rather than being conversation styles, I think what we were talking about was connectedness, that connective tissue between us, which is conversation, which is social media, the things that connect humans to each other is the way that we share our thoughts with each other and how we are interacting with each other, which is very different than before. Alan Helms (1:10:45): Yeah, it's different. And I'm just wondering what's happening again because we've got more ways to communicate than ever before. Is that part of the problem? I'd be interested to dive into this a little deeper and maybe isolate some of the problems and what causes that we think are happening if we truly believe it's an epidemic. Then I'm curious if the idea is to bridge the gap. We spent a lot of time talking about common issues and experiences we've all had and questions we've got about it. I'd love to, I don't know if we can summarize now, or if that would be a different podcast, to talk about ways that we've actually solved that problem. Are there ways to decrease loneliness? Because I don't think we've gone into too much of that today—how do we solve that problem? Jim Karwisch (1:11:50): We've kind of left a breadcrumb trail of our different thoughts about what would need to change. One of them was the weightedness that Jason brought up earlier: can you intentionally weigh someone's opinion differently and get yourself to have a different reaction and level of reaction so that you don't cut people out of your life or don't put up walls if you don't need to in order to move forward? Another is the level of intentionality and curiosity we can have around following up or understanding somebody better. If we feel lonely because we just don't like people, that's different than being lonely because we didn't feel safe and cut off all communication. If you wanted to start opening up those connections again, the weighting would come into it, right? The level of depth you already have with that person, the curiosity—all of those things would need to be warmed back up again. You would need to think, "I don't have people in my life. Why don't I?" Because all of this came so fast, it was so intense, I didn't feel safe. So I just shut everything down. If I wanted to start reversing that process, it would need to be about intentionally creating avenues of connection with other people. Who are those people? How do I choose who they are? Who do I invest my time in? And what do I stop investing my time in that's causing it to be worse? Jason Montoya (1:13:33): And let me piggyback on that. Intervene in people's lives. One powerful way is to create a safe place, and one way to create a safe place is to share your story. When I was isolated, I felt trapped, particularly with pornography. A friend shared his story of going through that and getting through it. I felt safe to share my struggle with him because he had suffered. He also intervened; he was there. So, intervening in people's lives, sharing our story—that requires being vulnerable and sharing scary things. I'll even use Jim as an example: some of it is providential intervention. Years ago, I was struggling with a situation, and Jim just happened to call me at the exact moment I needed him. I answered, and we had this conversation, and he was available. So, having conversation and relationship with people, and keeping that active, when those things happen, we're more likely to be there for the person when they need us and vice versa. Those are two powerful ways. Then I would tie in mentorship or just relationship. If you are struggling, having someone who can intervene in your life and walk alongside you. I moved to Atlanta from Arizona. We left everyone and everything we knew, and we were isolated and alone. I had a lot of toxic community, but I got to the point where I was like, "God, this isn't working. Help me." I started getting rid of the toxicity, and then God started bringing healthy people into my life to mentor and intervene. So, those are some practical things. If you want to get started, just find a guy, start getting lunch together once a month or once a week, and then add another guy, and all of a sudden, you've got a small group of people, and you work through your struggles together. That's an option. Jim Karwisch (1:15:49): What Jason said are all weighty, intentional things related to trying to make a situation different. That mentorship or asking somebody to lunch—you are investing in someone else, in that connection, and you're asking the other person to join you. If there is a severed connection between people and you want to regain it, that level of weightedness, importance, you're pouring yourself into somebody else in a way that's not superficial. I think the only way we can combat this extreme, fast-paced firehose of social media is to counteract it with intentional, individual, weighty, powerful, mentoring, supportive, and caring relationships. Jason Montoya (1:16:52): Alan, any final thoughts you want to share with us? Alan Helms (1:16:55): A couple of things I've tried to use to combat loneliness. One, which I talked about, is how Jason and I got somewhat connected: having a weekly group of solo entrepreneurs in the marketing field. We would meet weekly and often ended up talking about many different things other than marketing. That built a community and familiarity with each other, and it gave us a consistent weekly place to talk to someone we knew was going through a lot of the same types of situations, and we were trying to help each other out. So, there was a noble desire to that. So, that's one. I still struggle; it's kind of like telling someone the key to "don't be depressed, just feel happy." The key to combating depression is to not feel sad. I'm thirsty for something beyond that, which would be, if we talk about something like intentionality, it takes effort to be intentional. That person has to make that step. There are so many aspects of courage, energy, willingness, desire, or motivation to even get to that point. The problem I have with some of this conversation is that it doesn't get to the core of a lot of the motivation. Part of the challenge with loneliness is if you're cut off, if the onus is on you to stop being cut off from everyone, what are some things you can do to challenge that? It could be as extreme as changing your setting, moving to another city or town; that could have a good impact on some people and a bad impact on others, depending on whether you have the energy to go out and try to meet someone new. I don't know, my mind's just overwhelmed with a structured way to approach loneliness. If it is truly an epidemic, what do you do about it? Jim Karwisch (1:19:21): There's a difference between solving loneliness and improving the situation. I generally look for something small and experiment to try to make the situation better because solving for it feels so weighty and confusing that it would be almost impossible. So, my challenge to someone would probably be: if you imagined all those connections that might have been severed due to a lot of these different things we talked about today, if there was one person whose relationship was weighty enough that you felt you got severed with them, but you think it would be worth spending some time and reconnecting with them, what is one small thing you can do in the next couple of days or week that would get you connected with that person with some sort of gesture or communication that you would like to overcome the disconnection that's happened? Or if you just want a positive spin, you could just say, "Hey, I feel like we haven't talked in a million years. Can we get coffee?" For someone who feels completely and totally isolated and lonely, suddenly having someone they're going to have lunch with—the margin they would shift in loneliness would be almost immediate. So, I think the huge thing is, what are all the things we could do to make the situation better overall over time? That's a giant conversation we need to continue to have and keep digging at. The smaller conversation is what tomorrow looks like because we had this conversation today. Jason Montoya (1:21:03): I would add to that, you have to look for the lonely person in the sense that you're not going to see them. It may be someone with people around them, but they feel alone. You have to go deep enough to figure out what's happening. Sharing your story and being vulnerable makes it more likely they'll be willing to share. Also, if they're more lonely, they may not be as accessible. That's where intervention comes in; someone intervening in your life. If you feel lonely, one person can make a transformational difference. But it's usually going to require intentionality and intervention on their part—a providential connection where God reveals that. Jim Karwisch (1:21:40): Good. Thank you, Alan, for challenging this too. You really did uphold the point of view of the listener and held us to some really good answers and questions. So, thank you. Jason Montoya (1:21:40): Yeah, so Alan, tell us who you are and how people can connect with you if they're interested in learning more or reaching out to you. Alan Helms (1:22:01): I don't do a lot on social media, but my name's Alan Helms. I'm based in Atlanta. As you mentioned, Jason, I'm a CRM consultant. I do have a profile on LinkedIn, so you could find me there. I also have a company called Organic Endeavors, and you can find that at organicendeavors.com. Those are the two best places to find me. Jason Montoya (1:22:13): And your website is organic. So, LinkedIn and then organicendeavors.com. Who's the type of company or person that works with you? What's the problem they're having? Alan Helms (1:22:31): I do a lot of consulting around smaller sales and marketing teams for small companies, startups that are trying to grow. They usually invest in sales and marketing software called a CRM system for customer relationship management. I usually work with them to help them set that up so that their marketing campaigns and programs get adequately mapped into their software so they can collect the data they need to have insights and make better decisions around how their company is growing or not growing and in areas where they can improve. Jason Montoya (1:23:08): Jim, tell us who you are, what you do, and how people can connect with you. Jim Karwisch (1:23:11): I'm Jim Karwisch. I run a company called Untangled Narrative. You can reach that at untanglednarrative.com. I work with individuals one-on-one. I also work with small groups, and there's a community that we're in beta for right now; you can join it if you want to. You can find that at the website as well. You can also find me on social media pretty much anywhere at @jimproveuntangled. Jason Montoya (1:23:36): And he'll be launching the new podcast, Everything is Narrative, which I'll be participating in to break it in, get it going. And my name is Jason Scott Montoya. I work with organizations to help them amplify their income and their influence through internet marketing channels, content creation. And this has been a Share Life Academy workshop. I'm excited to have dived into this topic that requires much more time but has given us a tip of the iceberg. We'll see you on the next one. Jim Karwisch (1:23:58): Right, thanks. Alan Helms (1:24:03): Thank you.

![Four Powerful Ways Companies & Freelancers Can Effectively Work Together [Hubspot Guest Post]](/templates/yootheme/cache/ba/four-ways-work-together-bafd5ff9.jpeg)