The Long Game: If You Feel Like Giving Up, Watch This (Learn to Rest, Not to Quit!)

Think you're burned out and ready to quit? Think again!

We've all been there. You set big goals, you're pumped, then reality hits. You get tired. You hit a wall. And that little voice whispers, "Just quit." But what if that's the absolute worst thing you could do?

In this Share Life Academy workshop, Jim Karwisch of Untangled Narrative dives deep into "the long game"—strategies for long-term success, avoiding burnout, and staying motivated. We often quit when maybe "resting or taking a break, or pausing would have been the better thing to do." Jim explains how our own "mental stories we tell ourselves" can hold us back.

This conversation, with strategies for long-term success, avoiding burnout, and staying motivated, flips the script on what you think success looks like and how you define yourself along the way. Stop framing your goals in a way that isn't sustainable!

You’ll discover:

- Why the "I'm going to do this perfectly every day, forever" mindset is a trap that leads to quitting.

- How your identity can get tangled up in unsustainable visions and why that's a problem.

- Why "early success" can be a "hindrance to the long game" and what to do about it.

Are you making a "fatal mistake" by defining your success with a finish line instead of an "infinite game"?

Don't quit—rest, adjust, and learn the long game!

P.S. If you've been silently struggling, know this: you're not alone, and there's a smarter path forward.

- Watch: Click here to watch this discussion on YouTube directly, or click play on the embedded video above to begin streaming the interview. Click here to subscribe to my YouTube channel.

- Listen: Click here to listen on Spotify directly, or click play below to immediately begin streaming. You can also find this discussion on Pocket Casts, iTunes, Spotify, and wherever you listen to podcasts under the name Share Life: Systems and Stories to Live Better & Work Smarter or Jason Scott Montoya.

Additional Resource

- The Infinite Game by Simon Sinek (affiliate link)

- Path of the Freelancer: An Actionable Guide to Flourishing in Freelancing

- The Jump: From Chaos to Clarity for Your Striving Small Business

- From The Garden to the Cross: How Jesus' Harrowing Mission Restores Eternal Living Today

Who is Jim Karwisch?

Jim Karwisch is the founder of Untangled Narrative, where he helps people untangle the stories they live by, enabling them to move forward with clarity, alignment, and momentum. Through his work, Jim guides individuals and communities to rewrite the inner narratives that shape their choices, behaviors, and relationships.

With a background in storytelling, improvisation, coaching, corporate training, and group facilitation, Jim blends structure with spontaneity and logic with intuition. He's known for asking the right question at the right time.

When he's not working with clients or on his upcoming book, Your Untangled Narrative, Jim builds a community of thoughtful changemakers, develops narrative-based tools, and turns lessons from video games and pop culture into surprising insights about real life. He's a sci-fi fan, gamer, podcaster, and highland cow enthusiast who lives near Atlanta, Georgia, with his wife, son, mother-in-law, and a rotating cast of pets.

- You can sign up for his LinkedIn newsletter here.

What is the Share Life Academy?

The Share Life Academy is a community and place for us to develop ourselves, each other, and our organizations, and to get inspired. It is a place to help us escape survival mode, dream big, see clearly, and achieve great things together. One of our goals is to prioritize the important over the avalanche of urgency, to make sure we keep the ball moving forward on important projects that matter in the long run. It's also a place to discuss the important things that prevent us from finishing them and enable us to succeed.

Fill out the following form to register for this workshop and access the Share Life Academy. You can also click here to learn more.

Historical Event Details

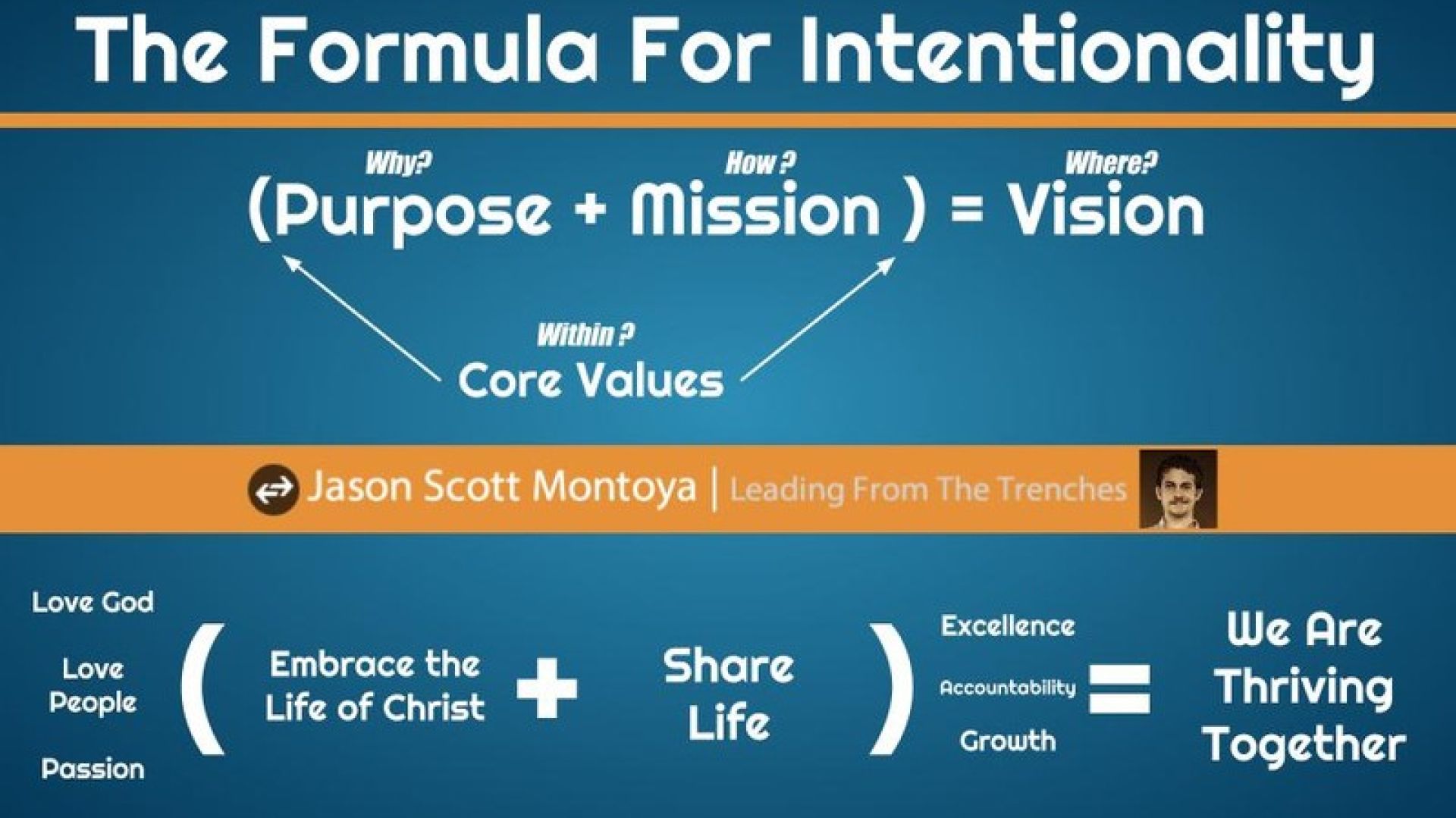

- When was this event? June 18th, 2025, 11am

- Where was this event? Virtual Stream via Riverside to YouTube.

Additional Resources

Workshop Transcript

Jason Montoya (00:00) If you get tired, learn to rest, not to quit. I love this quote because I think so often people get burned out, and they quit when maybe resting or taking a break or pausing would have been the better thing to do. Welcome to a ShareLife Academy workshop. I'm Jason Scott Montoya, and today I'm here with Jim Karwisch. Jim is the founder of a coaching company called Untangled Narrative. If you find yourself in a position where you want something, you have goals, but you just aren't actually making progress toward them, Jim will help you figure out what's holding you back—those mental barriers, those mental stories we tell ourselves. He'll help you figure out what it is, untangle it, and put it into a healthy story so that you can actually move toward what matters to you. Today, we're going to talk about the long game: strategies for long-term success, avoiding burnout, and staying motivated. This has been one of our ShareLife Academy workshops, and we've done several with Jim. We're going to be transitioning; next month in July, we'll be doing an episode on loneliness, and that'll be Jim's final episode for this series. Jim is actually launching his own podcast called "Everything is Narrative." People are allowed to jump into these podcast episodes and ask Jim their questions. Jim Karwisch (01:19) That's right. They can just submit a question if they want to if they're a little shy. Jason Montoya (01:25) That'll be happening starting on July 10th. That'll be the first one, and I'll be participating in that. On July 16th, we'll do our live stream for the ShareLife Academy workshop on the loneliness topic. Then, on July 17th, we'll actually dive deeper into the loneliness topic as part of Jim's podcast. So, this is going to be transitioning to a launch for Jim and his podcast, "Everything is Narrative." Check out the description and links below if you want to learn more about that. We'll be talking about that in the next episode as well. Without further ado, let's dive into our topic of the long game: strategies for long-term success, avoiding burnout, and staying motivated. I want to bring out a quote to kind of start the conversation. "If you get tired, learn to rest, not to quit." That comes from Banksy, who's a famous street artist. So, what are your thoughts when you hear that? I love this quote because so often people get burned out, and they quit when maybe resting or taking a break or pausing would have been the better thing to do. Jim Karwisch (02:44) The way that I think, based on my branding, based on "untangling of narratives," is that people don't realize they're setting themselves up at the beginning with something that is a goal or a truth for them that isn't sustainable the way that they have framed it in their minds. They frame it as, "I'm going to do this thing. I'm going to do it the best it can possibly be done, and I'm going to do it forever." Most recently, I saw this happen to a couple of people in the streaming world. I've got several friends that I've made through being on Twitch. They would hit things in their streaming life that caused them a disconnect. There was a misalignment between what they said they were going to do and what they actually are capable of doing. Different people have hit the same problem but have had different outcomes. For some of them, they just quit because they said, "I'm going to do this. If I don't do this perfectly every day that I say I'm going to, then I've failed, and I might as well not do this." Jim Karwisch (03:57) When we set ourselves up for what we want the future to be, maybe even a vision or a mission, I was using the example of streaming, right? "I'm going to be a streamer, and I'm going to define what streaming means. I'm going to define it that every day I stream. I'm one of those streamers. I'm very successful. I make lots of money. I have lots of followers. I get sponsorships, blah, blah, blah." At some point in time, I realized that that isn't sustainable. What I do next is very important because if I just say that's what streaming is, I'm not capable of it. Therefore, I'm not a streamer, so I quit. Jason Montoya (04:39) There's an identity piece there: "I'm not a streamer." I really want to just focus on that because I think that's the narrative you're digging into. Jim Karwisch (04:49) For me, narrative is identity. I think once you've started to say what you are or are not, you're pretty heavily tangled if it's not aligned with what's going to be sustainable for you. So, you could say, "Well, I'm going to quit because I'm not capable of doing this." The other part of it is, "I've got to slog through. I've got to give up my health. I've got to give up all of my free time. I've got to do everything because I do want to be this, and I said I was going to stream every day, so I am." And then burnout happens. Jason Montoya (05:26) Just like in the Dale Carnegie class, one of the things he says is, "Speak as if the thing is true before it's true." So, I am, like you said, "stream every day." That's kind of the idea: "I am a streamer who streams every day." If you're not doing it yet, then it's like you're casting the vision. Jim Karwisch (05:47) If you cast the vision of something that you haven't tested and don't know if it's sustainable or not, then as soon as you determine it not to be sustainable, you've now got a problem. Jason Montoya (05:58) That sustainability thing, I think, is huge because a lot of times we go into something in an unsustainable way, and we think, "Oh, I gotta quit." But what we could also do is just adjust it into a sustainable model or approach. Jim Karwisch (06:05) That's the process of untangling: to look at what you've got. Lay everything out on the table. See where things are unnecessarily dependent on one another. Then look at, is it so important that what you said you were going to do at the beginning is what you continue to do? Is that the most important thing to you? Some people might have an identity issue there because their word is their bond. They think if they say it and then they don't do that, they are not living truthfully or authentically. Or, "Now people are going to be disappointed if they don't see me every day because I promise to be on every day." I think sustainability is one of the big keys to that—what you said earlier on, "rest versus don't quit." Jim Karwisch (07:07) I also have watched people who have projects where they do need to take a break. When they get ready to take the break, in their mind, their audience is going to handle this so poorly. They're going to lose people if they stop, if they take a break or whatever. It turns out that the relationships they've created are so much stronger and more capable than they realize they've built over time. So, when they say, "Yeah, I'm going to go away for two weeks, and then I'll be back," and they come back, and everybody's there, they're like, "Yeah, you communicated clearly. You gave us realistic expectations. We know you're human." And maybe they come back, and they've adjusted. Jason Montoya (07:48) I want to use myself as an example here because I started getting serious about YouTube in January, and I got real aggressive about it. I was trying to figure out how this YouTube thing work: how hard is it to get monetized? My goal was to get monetized: a thousand subscribers, 4,000 watch hours. So, I thought, "Okay, I'll take the volume approach." I'll just create a lot of content. I knew that wasn't going to be sustainable long-term, but I was testing it out. Five months in, we're month six, I realized that it's going to be harder to get to the goal than I thought. It's probably going to take me a year or two to get there. So now I have to pivot how I'm going to do it in a way that's sustainable because of that reality. Jim Karwisch (09:01) And just to clarify, what was your emotional reaction to realizing that the long game here was going to be stretched into the future longer than you had originally thought? Jason Montoya (09:18) It was twofold. Part of it had to do with how I went into it. I went into it kind of with a hope: "If I could get this done in six months," that was my hope. I'm going to see if I can do that, based on my context and my resources and the way I was entering into it. I had that hope, but I also had the expectation: "It's probably not going to happen, but I'm going to try for it." That ended up being the case. "Okay, this isn't going to work out." Actually, one of the things that helped me with that, from an emotional standpoint, it wasn't devastating to me because I kind of went into it with the possibility. Part of it was I started out being a little bit more strategic and kind of long-term. Then I saw, in February, I had my most successful YouTube video ever. At the beginning of my second month, I got over 2,000 views, 130 watch hours, which is a lot for a YouTube video. So I was like, "Oh, this is kind of easy." Then I couldn't replicate that level of success again. I even did videos that I thought were even better, but they didn't perform at the same level. So, early success can actually be a hindrance to the long game. Jim Karwisch (10:41) If you look at it and you say, "Aha, I have succeeded. Now your expectation is I have arrived. So everything is easier now that I've arrived." For entrepreneurs, we know that that's a touchy area. Just because you have arrived and you're making a certain amount of money now doesn't mean that there won't be something that comes along, a stumbling block that causes you to reorganize everything and figure out a new product or a new approach or a new set of clients. So, if you have the expectation of "I have arrived, I am successful," and then you realize that's not repeatable, or at least it's not repeatable yet, because we know that about learning, when we go from being a complete novice, we will eventually, whatever it is you're trying to do, you will hit a point where you do it right by accident. It's not because you aren't better than you were when you started; you are. You got better, but you're not at the level where you can do whatever that thing is consistently yet. So, if you mistake that first success, you're like, "I got up on the bike, and I rode without training wheels, and I went all the way down the street. Now it's going to be easy forever." Nope. Your brain did something different, and now you're struggling to get back up on the bike again by yourself. Jason Montoya (12:28) That's really interesting because one of the examples that comes to mind is like the one-hit wonders in music—a band that just has this hit right off the bat, and then they disappear. I kind of wonder if having that hit is part of what makes them disappear. Jim Karwisch (12:59) It's a great example. The idea that one day in the future we're going to reach success, and when we do, life is going to be better for us if we just keep going. Well, if you think that day has arrived when you get that one hit and you change your mental landscape, you're like, "Okay, so now we have arrived," and everybody in the band starts to behave as though that's true. "We are now that level of success that we thought we'd be." But then it doesn't sustain. You changed things. Similar to being somebody who's dating long-term or has been engaged for a couple of years. Marriage, right? You're like, "Okay, well, now we're married, and so things clearly will be different now that we have done the ceremony." Wait, some of these problems are still here. Jason Montoya (13:33) Another example: whatever the goal is that you set. If you achieve the goal, it kind of removes the motivation. That's where having a goal that's more of like a habit, like "this is my habit," so with YouTube, my habit of creating a video, my goal is to create another video. So then it's more of a sustainable thing. The example that I think of is, I've been a movie extra in several movies, and I thought my goal was to get into a movie trailer. I wanted to make a movie trailer. Funny enough, I was successful in the movie "American Made." I made the movie trailer. After that, I think I did one or two movie extra things, but my motivation kind of died once I achieved it. Things, and the other part of it, is then COVID happened, so it was harder to be an extra. There was more friction. So my goal was accomplished. I had more friction, and I haven't really done a whole lot since then. If your goal is to get married, not to stay married, then that's probably why we all fail as spouses after the honeymoon period. Jim Karwisch (15:10) And the expectation shift. You might have been with people that lived together for four years as a couple before you got married. Then when you got married, you thought, "Okay, it doesn't matter. We've already been living together. So marriage is just going to be more of the same." But for one or both of the people involved, now being married changes how they expect the other person to behave. Now they're like, "Well, wait, no, now you're my husband, so you should be doing this." "Wait, you never said you wanted me to do that. Why didn't you say that while we were dating in these four years?" So, I think when we have markers set for certain things, we have to be careful about how we set those markers. Jim Karwisch (16:16) I'm pretty intentional for myself about mentally not being beholden to any one thing I've ever said that I'm going to do because I know I'm going to need to adapt at some point in time. So I don't feel bad about changing my goals around if it means that I'm going to be successful in a way that's going to help more people or allow me to pay my bills or whatever. I'll shift things, but I still want it to be aligned with core value, core vision, all of those things. If I don't know exactly what it is that I want, I don't have my vision set. If you just have a simple, "When I reached this goal, that's when it'll be done." Sadly, now it's done. Now you don't have the motivation anymore. You got the dopamine hit, but now you don't have the drive. Jason Montoya (17:06) I think it can be a double-edged sword. For my freelancing, I've kind of hit my income goal for four or five years now, and then I've just sustained that. I could actually grow it a little bit if I need to make extra money for something. So I have a specific reason to get more. I work extra hours for this thing. It creates a container where I can work part-time and earn six figures, right? So I have all this extra time to do stuff like this, to do the podcast, to write my books, to all that. That was the design, the goal, to create a sustainable kind of ecosystem. I would probably have, if I had to just do the freelancing without the second piece of it, it would be hard for me to sustain because the freelancing piece is a bit of a duty. I have to provide for my family, and so on and so forth. I learn and grow, and there are some aspects of it that are interesting and exciting, but really where my heart is is on my idea business. Creating this kind of self-reinforcing ecosystem where I can do both makes it more sustainable. That's one of the things I learned, even in Noodlehead, when I had my marketing company. What I realized is that there are things that I'm looking for in my work and my vocation to give me meaning and motivation. If my job or my company only gives me two or three of the five things, then I need to do the other two or three things on the side or as a hobby or on the weekend or at night so that I have the complete package. If something doesn't give me the complete package, I can get the complete package if I just put the pieces of the puzzle together. And that makes it more sustainable. Jim Karwisch (19:01) If your needs aren't getting met, then you're going to have another problem with momentum. If your needs aren't getting met, that might be another possible reason for burnout. Even if the intensity of what you're doing, like you drop the number of hours that you're doing your day job, but you don't have something to fill in the other hours, you're not doing the things that make you feel complete, that take care of those other parts of you. Then those empty hours are not a blessing. They're just empty. Jason Montoya (19:42) If I didn't have something to put in those, then I'd be like, "What do I do with this time?" I think a lot of people struggle with that when they retire. Jim Karwisch (19:49) The narrative around retirement is a tough one because people will say, "When I retire, blank will be true. When I retire, this will be true. When I retired, that will be true." I was talking to a family friend the other day, and they said they were getting ready to retire, and they bought a camper, an RV. They were all excited about retirement, about being able to travel. Then they realized that the level of responsibility they had in the town they were in and in the house they were in would not allow them to just hop in the RV and go. They had not created a path to get to that place where the RV was. So, in their mind, it was retirement and owning the RV that were the key components. They had done both of those. They bought the RV like they said they would, and they retired like they said they would. Now the expectation is that "I will now be a person who travels." Jason Montoya (20:55) I wrote this book, Path of Freelancer, for freelancers, a blueprint on how to be successful. I talk about the expectation, like they had this dream, and then the reality they were living didn't match it. I had my marketing company, I shut it down. I didn't know what I was going to do next. I assumed I was going to have to get a job. So, I had some expectations that I thought having a job I was going to lose. But if I had a job, then I'm going to lose my freedom, I'm going to lose my financial upside. So I started to think about it like, "Wait a second, I could still have those things. Just because you're an employee doesn't mean you couldn't have those things." So, how could I get that if I were an employee? That led me to this mindset that I actually ended up using as a freelancer, which was, "I'm the employee you wish you had, but you can't have." I actually took the expectation and turned it into an advantage. It can go the other way. A lot of people go into business, and this was me when I started my company: I thought I was going to be free, I was going to have freedom, and I actually became enslaved in the business financially and with my time. The same is true with freelancing. Really, anything—it could be a company that you work as an employee, or it could be a business you start—you can become enslaved. Just because it seems free doesn't mean you will be free. It's all about how you structure it, design it, and operate it. That's kind of similar to what you're describing: you can have a dream, whatever your dream is, like you might have actually put yourself in a situation where you can't have the dream because you'd be living the dream already. If they had this RV life they wanted to do, they could have been living it already, maybe part-time. Then when they retired, they could have gone into it more. That would allow them to transition their responsibilities in a way that would allow them to do that or not take them on. Jim Karwisch (23:02) This is all in alignment, I think, because we mentioned burnout. We mentioned losing momentum. If the long game is set up properly, I think the ability to change something. Whenever I'm coaching people, I try my best to figure out not exactly what the path will look like for a certain amount of time, but to try and find a cardinal direction. We understand that no matter what happens, as long as we're going that way, we're doing the right thing. Then if you need to navigate, if you need to make small little adjustments as you go along, pull the raft out of the river and walk with the raft above your heads for two miles and then get back in the water again. If that's failing, then you failed, right? But if that's a way to complete what you were trying to do. "We didn't die in the river, right? We didn't realize that this particular waterfall and these particular rapids and the speed and everything, we're probably not going to make it through if all of us went over that. Years ago, it was these conditions, and we thought it was going to be this. We continue on, we walk a couple of miles with the raft above our heads. We put it back in the water, and we continue on." As long as we're still moving in the right direction and we don't determine that we failed somehow, we can live to see the next day, and we can complete the journey that we were on. But it requires us to be okay with doing something that's not in the original vision or that isn't the steps that we laid out when we perfectly charted what success would look like. Jason Montoya (24:36) I want to kind of give an example of one of my applications here that I think ties into what you said about setting a goal that once you accomplish it, it pulls the motivational weight out. Simon Sinek has the book, Infinite Game, and he talks about the idea of a finite game and an infinite game. The finite game is having a goal that, like, to win the Super Bowl, then you win the Super Bowl, and then now what? You earn a certain amount of money, now what? You get married, now what? An infinite game is the idea where you are committing to a goal that is sustaining, like you sustain this thing. I want to tether that into this idea of effective political movements. I was watching this video the other day where political movements that are based on an antagonism, like "I'm against you" or "I'm against this idea," when they actually succeed, they end up failing and faltering and dying because they have nothing to go beyond that victory. It's a finite game where they win, perhaps like a political victory, but then they just start to decay. What you have to have is a positive vision for the future and not just an anti-vision that is against someone or something because that will sustain you after you achieve the goal of victory in the case of power. That can be true in a business or relationship, but having a proactive vision for this future state that you want to bring people to, people want to participate in and be a part of. That's a really important piece of playing the long game. Jim Karwisch (26:49) One narrative thing that popped up when you said not having an anti-vision. The idea that there's a revenge story. Someone is now going to dedicate their life to seeking revenge, and in whatever story it is, usually when the person actually enacts the revenge, they're like, "Wait, what is my life now? I put everything into doing this thing. I completed it, but I'm 40 years old. I've got plenty of life left. What happens now?" Redefining what happens next—that could be the breakdown point where none of the things that you really wanted for your life are going to happen because you didn't have a vision for it. You had a specific mile marker that was, "I've succeeded if." Those bands that if we get a hit single, we've made it. Everything starts to become easier now. Everybody starts to behave differently. The chemistry is different inside the band. People who had minor frustrations or major frustrations, but they just kind of waved them off over time until they got famous. Now they start to act differently. People can't work together as well as they used to. So, it's all, "Just hold together until this point when everything will be different," or "We're finished when we hit this point, and then everything will be easy." So I think having the right mindset and the right expectations about what the long game really is and what the infinite game, like you were just talking about, is. Jason Montoya (28:45) One thing I would want to piggyback on that is having a personal vision. Have one for your business. Have one for your work as well, but I'll talk about the personal vision because, if you don't have one and you need help, Jim can help you craft a personal vision statement. I think about the vision as the "where"—where are we going? I've written my personal vision statement; it's pretty simple. It's "we're thriving." It's "thriving together." I can simplify it in two words: "thriving together," and that can apply to anything. So, our podcast here, are we thriving together? Are we flourishing? That's kind of that first, and then are we together? Are we isolated? Are we separated? I'm moving towards that in everything I do, in every part of my life. That's an infinite game. And my mission is to share life. It's to give and to receive what others have to give me and what I have to share with others. It's a mutual reciprocal win-win benefit, and that can manifest a lot of things, but that's why the podcast is called Share Life Podcast, why the Academy is called Share Life Academy. It's actually based on my mission statement. These are these infinite game, these sort of long game ideas that no matter what I'm doing, whether I'm blogging or YouTubing or podcasting or working with a client, with a freelance client, that's my mission and that's my vision. If you have that, then it creates this kind of container that anything you're doing, whether you're a parent or employee or a freelancer or just a neighbor, you know, how am I embodying that? And it's also part of it. Part of it can be scary to do that. And I think some of the resistance comes from like it creates accountability. So now when Jim sees me like, "Jason, you're not sharing, you're hoarding," now I'm accountable because I'm public about this. But it's also what's required—accountability is what's required to actually get stuff done, to be effective at achieving the vision. It's like a double-edged sword. Jim Karwisch (30:54) You brought up accountability, and that's a huge thing. I hadn't been preparing for this topic today, I hadn't really considered accountability, but if you are being reminded by others what your mission is really about, those other people holding you accountable, there's being held accountable to, "I said I'd do this, and you're reminding me that I said I would do it." So I'm being held accountable, which feels kind of like, "I'm going to, this is, this is a thing I'm doing," you know, it's kind of tough love kind of a thing, but there's also the part of accountability, which is to be reminded about who you are and why you're doing this. And so, "Hold me accountable to who I want to be, hold me accountable to who you know me to be." And that's the types of intervention that have been the most positive in my life is somebody saying, "I see that you've done this thing, and that's really cool that you achieved it. I don't know that that really has much to do with who you're trying to be." "I don't know that it has that much to contribute toward your life and what you're trying to do." And it's like, "Wow. You're right. I mean, that was a thing that I thought would be neat to do, but it doesn't contribute." So if I keep doing that, just dive in and just do that thing for a long period of time. I might be so far away, like whenever you go into the ocean at the beach and the tide kind of pulls you down the beach and you don't realize it. So when you step back onto the beach again, you're like, "Oh, I'm like, I don't remember exactly where my blanket is or where any of my stuff is. I've gotten so, so pulled." Jason Montoya (32:37) I think that's such a huge thing. And I think I would give this as like a tip to anyone. It's like, when you give advice, make sure it's in line with the vision, with the values. So if your goal, Jim, is to drive to Disneyland in California, and I'm like, "Jim, here's how you get to Disney World in Florida," I'm gonna give you the wrong advice. Maybe we have a conversation why you should go to one or the other. Maybe that would be worth it. But I shouldn't give you advice on how to get to Disney World if you're not even trying to go there. So I think that's the type of advice people give all the time to people. It's completely unhinged. But if you're like, "Hey, I want to go get Mexican food," and I start telling you all these Italian restaurants, I'm not helping you. And so those are obvious examples. But people do that all the time. One of the things that's required to actually give helpful advice or helpful feedback or helpful accountability is to actually know the person enough; you have to know the values and the vision so that you can actually do that. I think it's super powerful. And I think it's a double-edged sword. You gotta clarify that for yourself so that when people give you feedback and advice, you know whether to listen to it or not. Because a lot of people, they criticize or give you feedback or say things that's just trash. But if you don't have clarity, you don't know it's trash, and so you might give it more weight than you should. Jim Karwisch (34:09) And also the type of person that you are, people will give advice about... The advice comes from correlation, not causation, right? So they'll say, "People who are extremely wealthy have these five things in common." Here's my clickbait, get in here, let me tell you what these five things are. And maybe one or two of them really had a lot to do with their success. And the other things are just idiosyncrasies of that human being and what they like to do. And you're like, "Well, if I alter my behavior and I do that thing, that doesn't put me any closer to being where that person is." So just because I want to have an end result that is similar to the other person, their vision might not be like when we're, we're on the same path and we're going to walk together and protect each other as we get to this city. But when we get to the city, we have different purposes for being there. So it's so important when you align yourself with somebody else, when you hold somebody accountable, when you give people advice that you're giving it to the version, like you're feeding that person's reality and considering that it might be different than your own. The number of people that live very, very simple lives, and when I say simple is they don't spend a whole lot of time questioning things, they just spend a lot of time doing things. And they'll get very surprised when somebody will behave in a way that seems counterintuitive or against the principles of whatever it was they've assumed this whole time. "I thought you and I were aligned on this." "Well, no, what happened was was we never questioned it and that never popped up for us and never came up. But as soon as it did, we had major trouble because I didn't know what your vision actually was. I just made assumptions that you were like me. And then when we reached the city, you were an revenge story and I was in an abundance story." Jason Montoya (36:06) I have a fun example of that. I kind of inherited the party of Republicans just growing up and in the ecosystems I was in. I still identify as one, but I never got on the Trump train. So I've been very vocal in my opposition to Trump because of a lot of my values and my Christian faith. I saw him as the antithesis of that. And so that kind of has played out. In 2016 and 2020, I kind of, in terms of my vote and some of my private activities, I involved myself. I'm making a lot of assumptions, but maybe I don't even know. And so he, I can't remember exactly what he said, but he's like, "Who did you vote for the last few elections and are you even a Republican?" 'Cause I think at that point I hadn't clarified that, but so I kind of walked through like, "Hey, I was a lifelong Republican. I voted Republican. And then in 2016, I did not, I didn't vote for Trump, although I voted Republican down ballot, and here's why." And then I talked about 2020, "And here's why," and then the evolution. And so I kind of clarified those things, but it was that same kind of thing. And I had that same type of thing with him, like, "Wait a second, we do like in a lot of, in some fundamental ways, we are very different in our values and our vision." And we just haven't been, while we've been in situations and environments where those have created a tension, the tension hasn't been so extreme that it created a break. But this was the situation where that kind of came to the surface. And because of my voice by speaking out, I created a lot of tension for friends and family that knew me that then felt the tension they didn't feel before. Because when it's your enemy, like, the Democrats, of course they hate Trump. But when it's your ally, like, it creates a tension. And a lot of them struggled with that tension. And now they feel the tension I've been feeling the whole time. Jim Karwisch (38:48) Yeah, I think we were just having a conversation the other day. It was during a client session. The topic came up of how marriages and preparing to be married. There's a lot of those things should be applied to businesses when two people are going to go into business together and the things that you need to know about somebody before you marry them. The questions you should ask, the alignment you should seek, the values that you should uncover. Those need to happen in businesses too. But people will just be like, "You know what? We both love remote control cars, and we have a passion for building faster remote control cars. Let's get into business together." And then the money starts coming in, and you're like, "That's a person who only cares about blank. I care about that a little bit, but I also care about this and this and this. There's so many parts to this for me. And they just care about this one thing, and it's everything to them. And that's going to really cause problems for us in the future of this business." So the types of questions, there are no right and wrong questions in that area, as long as they're leading to you understanding the values and the vision of that person. And I think people get really hurt when they marry somebody who they discover after a while of being married, "We don't seem to be moving in the direction that I thought we were moving in. Why haven't we started to go that way?" And they talked to their spouse, and their spouses are befuddled as to what they even mean. "Why did you think we would even, why did you think that was going to be something we would do? I've never said I want that." "Well, you've never said you didn't want it, right? We never clarified. We never came to the same understanding about our future together." And that's... Jason Montoya (40:47) And that kind of comes down to like, you're getting what you want out of the relationship. Sometimes you might want to skip that piece because you don't want to rock the boat, so to speak, right? You're getting what you want, whatever that might be for each person. And so you just move forward, and then you end up, years later it's like, "Okay, we kind of fell apart there, but we might." And this kind of gets to one of the advice I've heard in terms of how to have a successful marriage. It's like you prevent bad marriages. So you don't get married unless you have that alignment. And in Christianity we have this idea called "equally yoked," where the fundamentals, you're on the same page, and those hold you together through all the differences on everything else. I want to shift to a little bit of a tactical, some tactical pieces. In terms of the long game and how to sustain. One of the things I wrote about this in Path of the Freelancer, one of the things that differentiates you as a freelancer or as a business is doing hard things because hard things are naturally going to filter people out. So when you talk about the long game, if you talk about like a 5k, only a certain number of people are going to do a 5k, and only a certain number of people are going to do a 20k, and only a certain number, and then a piece, some of those people are going to fall off, and some will do an Ironman. By the time you get to Ironman, it's like a really small segment of the larger segment, right? And so the idea is if you're willing to do the hard thing, like that'll differentiate you and give you an advantage, and that's an opportunity for you as a freelancer, as a business. But to do the hard thing, you have to be fully committed. Because you ain't doing an Ironman unless you're like all in, you know, like it's rough. So I had this idea, I thinking about, I was listening to this podcast episode, just about, there's like five million podcasts, and most podcasts won't reach 50 episodes. Most won't. So if you do a podcast and you reach 50 episodes, you are now, I don't know what the percentile is, let's say 20%. And if you go to 100 episodes, it drops even more. I think if you, there are only like 100,000, out of the five million, only like 100,000 of the podcasts have more than 100 episodes. So you, and then if you keep going to 200 and 500, like it just keeps dropping. And so when I started my freelancing business, I was able to have success within a couple years, but I really wanted to build a second business, which is the blogging, the podcasting, the books and all that. And I really, that was my mission was like, I'm gonna play the long game. I'm doing this until I die, you know, like so I'm just gonna keep going at a sustainable rate. And I've over 600 blog posts. I've got 150 podcast episodes or so. I've got a bunch of YouTube videos. So I'm just, I'm keeping the machine going, and that's the foundation of this content creation business is I'm just gonna outrun or outwalk everyone because if I just walk long enough, you know, it's that I'm gonna win, you know, if it's about who walks the longest. So that's one of the practical pieces. What are your thoughts on that? Jim Karwisch (44:03) Yeah. I wanted to say, "Just keep swimming," from Dory. Jason Montoya (44:10) And, you know, you gotta pivot and evolve so that it's sustainable. I think those two come together. You just keep going in a sustainable way. You keep going, and when it's not sustainable, you have to pivot. Otherwise, it'll break apart. But as long as you keep those two things in check, then I think that's... Jim Karwisch (44:31) Sometimes you have to figure out how to enjoy this present iteration. This might be a hard slog to get through this particular draft. "I'm on draft three, and this is easier than draft two, but it still seems like it's going on for so long." How do I try to enjoy this process to get myself to be present and really to make this a part of my life that I want to be living, not just a thing I have to do to get to the end result? So sometimes I have to trick myself, and I have to have different, you know, I have to change up. Where do I write the next version of this? Just in my house, the difference between writing something brand new that I'm making a first draft of, and going upstairs and getting on the couch with my laptop. There's a completely different experience all of a sudden, right? Just changing my environment changed the way that I felt, and it changed the way that I felt changed what it was to do that work. So, there's all sorts of different things that you can alter while still being consistent and sustaining over time. Jim Karwisch (50:06) There are people you can bring in for this next mile that are going to run with you. They can't run an Ironman because they're not built for running an Ironman, but they can come in and run that mile with you and be alongside you and give you encouragement and those types of things. So, who can you bring in for this particular difficult thing? How can you change the difficult thing so it's still getting done, but you're doing it in a way that feels at least somewhat different? I'm ADHD, so things feeling novel. If I were doing that, I might make a print of the draft just so I could hold the book in my hands and feel the feeling of having done something so that that kicks in. And then I feel like I can continue to move forward in the process. Jason Montoya (50:51) Having the proof, it feels like, "Wow, I've been working on this thing for four years, but it's all like in the digital ones and zeros." But having it real, "Okay, now it's another level of motivation," and I've got it. But both this book and this book, The Jump, my mobile phone has been a huge asset. So, to your point about changing your context, removing friction, if you can figure out a way, like everyone's using their phone to watch TikToks and Instagram reels and stuff, you could also be writing a book. You could also be writing a blog post. You could also, I mean, you can't, there are probably certain things you couldn't do, depending on the environment. Maybe you can record a video, but maybe sometimes you can't, so you can write something. Changing that piece, the Share Life Academy, I launched it in part to help me keep moving this book forward. That's the idea with the Share Life Academy is, how do you keep the important thing moving forward when the urgent things keep coming up, right? And so, the Academy just as a place, it creates a tension to keep those things moving forward, and then anyone that wants to participate can also benefit from that same tension. And so, like you said, who do you surround yourself with? There's ways that you can do that. And so, any final thoughts on this idea of the long game to close us out here? Jim Karwisch (52:16) Just think as many times as it can be reiterated, the idea of checking in, comparing your current progress and your current milestone back with your original vision, just make sure, "Am I still going in the direction I mean to be going in?" Is the thing that I'm, where I feel stuck, where I feel off, or should I quit, or any of those types of things, take a minute and just look back at the reason that you started doing it to begin with. Is maybe some of your motivation tapering off because you didn't shape the goal quite right, or it wasn't aligned quite right, or you didn't have enough people in community with you invested or holding you accountable, or there's not enough dopamine running in your brain, and so you need to change how you're working on whatever it is? Checking in with yourself, having moments where you're not just trudging away in the wrong direction over time. Jason Montoya (53:16) I like that. Moving in the right direction, adjusting along the way, and keeping fueled along the way towards the end game and sustaining that end game as time unfolds. That's the long game. Jim Karwisch (53:30) That was long, long game podcast. Jason Montoya (53:32) Tell us if this has been helpful, if there's any interesting insights you've garnered along the way. I want to remind you, this is part of the Share Life podcast and part of the Share Life Academy. If you're interested in the Share Life Academy, I'll put a link to that so you can learn more about it. Join our Discord channel and the link I provide. Jim, tell us who you are, how people can connect with you. Jim Karwisch (53:53) I'm Jim from Untangled on social media, and I'm the founder and owner of untanglednarrative.com. So check out the website, say hi on social media, I've got a Discord as well. Jason Montoya (54:07) So your website, you're on Discord, and then this "Everything is Narrative" podcast will start July 10th. Jim Karwisch (54:14) July 10th. That's right. Check out untanglednarrative.com, and we'll have something on the front page about this new project. Jason Montoya (54:20) Okay, so check out that, we'll have a link. If you want to join us for that first session, July 17th will be a follow-up session to the next Share Life Academy workshop, which will dive into loneliness. We'll do a deeper dive in Jim's podcast, "Everything is Narrative," and that'll kick off his series, which he'll be doing every week. And you can be a guest or you can submit questions, and so there'll be more details on untanglednarrative.com. I'm Jason Scott Montoya. This has been another episode of the Share Life podcast. You can learn more about this podcast as well as check out the many hundreds and maybe even thousand resources that are on my website at jasonscottmontoya.com. And check out my books, The Jump for Small Business Owners, Path of the Freelancer for Freelancers, and hopefully soon Christians can read my book From the Garden to the Cross. We'll see you now in the next one. Jim Karwisch (55:13) Yeah. Thanks everybody.

![Four Powerful Ways Companies & Freelancers Can Effectively Work Together [Hubspot Guest Post]](/templates/yootheme/cache/ba/four-ways-work-together-bafd5ff9.jpeg)