How To Talk With Drastically Different People Without Losing Your Mind: From Fact Flinging to Story Sharing

Prefer to listen? Listen to the audio version of this blog below. Click here if it's not working.

If you're arguing with someone quite different than you (who does not share your stories and values) about facts, you could end up filling yourself with anxiety and getting deeply frustrated. If you see your rival's point of view as dangerous to yourself, your community, or your country, you’re also going to be inclined to act more controlling by their strong stance exhibiting behaviors that seem unlike you. Doubling down on your existing approach may end up making the situation and your relationships worse; it has for me in many situations.

If you want to make a difference and affect change, it will require approaching things in a way that is effective at accomplishing your goal. And to be effective means to better understand the real dynamic at play.

From personal experiences, research on helping people get out of cults, and the study of evil propaganda, I've discovered how facts often don’t matter because information we receive is nested inside the story we tell ourselves (or if you prefer differing words, beliefs, perspective, paradigm, or worldview).

Stories and beliefs make facts relevant (or irrelevant) to us. If a house is burning down across the world, it's not relevant. If it's my house that is burning, it's urgently relevant. That's because of our values and the story we tell.

For those in allegiance to a story or a storyteller, facts will likely only further entrench them into their story. In many cases, more facts that counter their perspective will likely radicalize them as well.

Usually for people to change their minds, they need to voluntarily seek out (or at least invite) competing stories. They’ll need a story they value that provides a pathway out of their locked story (like valuing truth over being right). If they lack this pathway, it's likely only seeing contradiction or being appropriately challenged that will provide them an opportunity pathway out.

I’ve known this intellectually and practically at a level, but I've recently and more fully stepped into it as the stakes and emotions have increased with our societal polarization and fossilization.

It has been liberating and anxiety-reducing to see that we are arguing over stories and not facts (which there is a practically unlimited amount of). And, this understanding of our story fighting creates a pathway on how to have productive conversations with others without losing our minds or souls in the process.

If we can identify the core issue, the core desires around that issue, and the story we tell that makes sense of these things, we now have competing stories that we can compare.

Now when I engage with people, I let them know that what we're fighting about is our stories of the world and use the time not to throw facts at each other, but rather to dive into these stories.

It's important to realize, we have embraced the stories we have because they gave us something. They worked for us in some way. Letting go is hard. But it's often the only way forward.

But, let's dive deeper into the concept before we talk about story sharing.

Our Desires Drive Us Towards The Stories We Tell

“What is the source of wars and fights among you? Don’t they come from your passions that wage war within you? You desire and do not have. You murder and covet and cannot obtain. You fight and wage war. You do not have because you do not ask. You ask and don’t receive because you ask with wrong motives, so that you may spend it on your pleasures.” - James 4:1-3 CSB

There is an unlimited number of facts that people can collect and process. The relevance (or irrelevance) of facts is based on the story we're telling ourselves and each other. This is part of why there is no such thing as unbiased or neutral. Every point of view, including the proposed unbiased or neutral point of view has a bias, it's just a different type of bias and perspective.

So what's behind this?

Humans are creatures that want. And we’re tribal so if we and our tribe, get what we want, we’re satisfied. In a society of many tribes, there are more competing desires, and thus competing stories.

A helpful question in debates is to tell the other person what you want. It's to ask them what they want. And it's to discover what the people involved in the issue we're discussing want.

Right now in our society, we’re in an era where people want vastly different and competing things (or order of things). And as a result of those competing wants, we are presenting and living competing stories of reality. These are the stories we tell ourselves to reinforce that what we want is good.

At the end of the day, we each place our faith in a story (and the storyteller) and then build our cases for that story. And we build our life on it.

Sometimes the stories are true, other times they are false. Often they are incomplete.

Our story, the inner narrative (beliefs we hold and follow) directs which facts we seek out and which we ignore. Our story guides us as to how we process those facts and derive our conclusions. The way we live our lives is by living out these stories and beliefs, often how we live differs from what we verbalize.

We are most attracted to the stories (and storytellers) that match what we want most. Simply put we like stories that give us what we want and tell us what we want to hear.

Our stories clash when what we want differs from what others want.

How Stories Trump Facts

Let's explore an example.

First, ask yourself, what's the story you tell about yourself? What about your family? Your marriage? Your parenting? Your work? Your community?

Take the narratives up a notch. What's the story you tell about Democrats? Republicans? The border and immigration? The last election? Jan 6? The economy? The next election?

These stories shape how we see the events in our country and across the world.

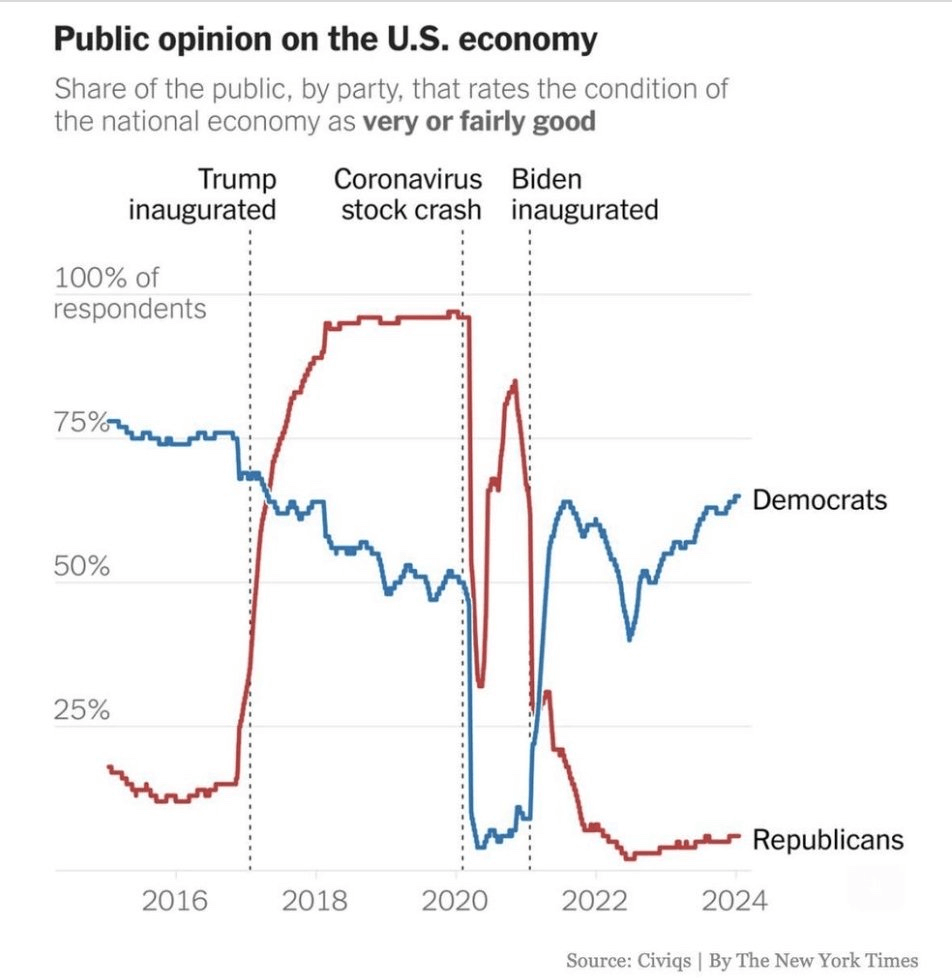

The following is an insight from the New York Times about public opinion of the US Economy. Since 2016, Republicans and Democrats have been telling themselves two different stories.

Same country, same economy, but different stories by differing groups.

The key here is the lack of time required for the stories to flip after 2016. Scott Sumner highlights below, this reality in the following quote from his blog post, There's nothing "WEIRD" About Conspiracy Theories.

“Polls show that the views of Democrats and Republicans on the state of the economy immediately flipped after the 2016 election, before there was even time for the actual economy to change very much.”

The story flipped when the Republican leader took power. And it flipped back when the Democratic leaders took power in 2020.

Facts don't matter. Stories matter. And then we find the facts to affirm the stories we've placed our faith in. (Note: in many cases, the stories may differ because we experience reality differently, which is why the amount of time before the perception changed is a key insight here).

Facts (and real-life pressures) can press in on us, when our stories are so out of touch with reality, that this information challenges our story. But in a world of bespoke realities, this is more challenging than ever to get challenged because we can be fed information (and seek that out specifically) which constantly reaffirms the stories that give us what we want to hear.

Elevating: Understanding Allegiance & Idols

Stories are derived from our allegiances. These allegiances take multiple forms.

- The allegiance for some, is personal. It's about winning, and/or getting what is desired; which could be survival, pleasure, purpose, or achievement.

- Another form of allegiance is social and tribal. These people want to belong in a community and perhaps move up the hierarchy of it. In this case, they go along with the group so they don't become alienated from it or so they don't risk alienating others in it (appeasement).

- For the rest, their allegiance is ideological, a collection of core stories for how they see the world. If someone has an ideology that the government is bad (or good), they'll align with leaders and powers that share their ideology. The more we're around those who share our values, the more we come to believe that is the only way to see the world and it can lead to us becoming delusional about our dependencies on others who see the world differently.

Those are the three main categories of allegiance stories. Understanding the source of a person’s story (as well as our own) and the type of story they’re telling is important for making conversational progress. When we operate at the story level, we elevate above the fact flinging into a more productive plane. When we don't share the same stories, fact-flinging is likely to further alienate us from those who have placed their faith in different stories.

One Shift We Can Make: Get Clarity On Our Desires & Stories

If we look at our stories, we can often find the deeper story (belief) that is guiding the little stories (beliefs). If we understand what we want or don't want (fear & contempt), we can make sense of why we like certain stories over others.

That which we make the highest value in our life, that which we want most, is the technical description of our god.

As a Christian, if that highest value is anyone or anything other than Jesus, we would call it an idol. An idol is something we put in place of the one true God. Christians see idols as a negative thing but an irresistible way of living. Whether you look at it that way or another, it’s invaluable to understand, that what we place in that highest position drives the stories we embrace and tell.

It will be hard to have conversations with others at the story level if we fail to understand our desires, allegiances, storytellers, and stories. So before you start talking stories with others, get clear on your core story and the story layers that build on it.

When we do this, we can rapidly move to the core issues and have productive conversations with others.

Here are some more tips on how to do that.

Three Ways We Can Make Conversational Progress With Others Who Live Different Stories

Sharing our stories and testing these stories is how we can make progress when it seems like we're gridlocked. We often make our claims with the assumption that our story is obvious, but that is not always the case. It's less the case these days.

Operating with fewer assumptions will enable us to talk at the story level.

Here are some ways to do it.

1. Story Sharing: What's Your Story & Here Is Mine

"If we can establish that common ground, namely that all of us are plurals, then that will allow us to frame people with whom we potentially disagree as people with backstories that we should try to understand... We should try to understand because they have something to teach us about what it means to be human." - Irshad Manji, How To Persuade Your "Enemy", The Good Fight With Yascha Mounk

Sharing can go either way. We can share OUR wants and stories with the person we're talking with or we can learn about THEIR wants and story. Often when we see the tip of the iceberg, there has been an extended journey that led them to the place they're at. Same for us. Without both sides understanding each other stories, it can be hard to empathize and hard to find ways to collaborate. And often, the initiator usually has to be the one to go first.

The next time you engage with someone who sees the world so dramatically different, figure out their story and who is telling those stories. Discover their allegiances and why they value those storytellers. Tell them about your allegiances and how your story guides you.

A conversational starting point: tell me about the journey you went on that led you to that perspective.

2. Story Exploring: How Does Your Story Work Here & Here's What My Story Predicts There

It's powerful to understand someone's storyteller and story. But it doesn't have to stop there.

Place yourself in their story and explore. This is called cognitive empathy. Once you're in their story, ask about the things that don't make sense. For example, I've gone into the story of others and saw a difference between how they are acting versus how I would act if I believed what they believed. This difference is a way to explore the story and learn more details. This exercise has helped me to more deeply understand the story and that person's unique considerations or limitations.

And if their story is problematic, this exercise can help find blind spots (of which some will be open to hearing and others not). At that point, they can further develop their story into a more complete one that addresses the blind spots, if they so desire. Or, it can provide an opportunity for them to shift out of their story into a better alternative one.

Another way to explore stories is to share our story and open it up for scrutiny. I’d recommend starting in safer environments, but then working towards sharing it with actively antagonistic folks (assuming you want the most true story, which not everyone wants).

The strongest stories will sustain the most difficult of challenges so this approach is putting your story to the test. If you are vocal about your story and what you expect to happen based on it, your model can now be proven true or false. If it's proven correct, it demonstrates its strength which can persuade people. And, there is little that is more powerful than a strong and proven story that someone lives themselves. If it fails to predict correctly, then you can reevaluate your story to improve it for the future.

3. Talk At the Story Level & Focus On The Central Story (or point of it)

"...our information ecosystem no longer assists us in reaching consensus. In fact, it structurally discourages it, and instead facilitates a dissensus of bespoke pseudo-realities." - Renee DiResta, Mediating Consent

We no longer share the same story. And as a result, our society has fractured.

Perhaps one way to think of of us having these fundamentally differing stories is that we’re speaking two different languages and to effectively communicate, we have to learn how to translate what we’re saying and focus on the pieces that are of the utmost importance. Stories are the way we can compare and contrast our differences.

"A story is a hierarchy of values. " Jordan Peterson

Ideally, before we make that leap of faith in a story, we set forth both stories and their cases and figure out which one is more true. The goal should be to place our faith in the most true story and its storytellers, but we often place it in false stories or probably more often, just incomplete stories.

It’s hard to back away from a false story because of our pride and selfishness so this is why it's good to do the discovery (including the best counter-arguments) before jumping in.

“For which of you, wanting to build a tower, doesn’t first sit down and calculate the cost to see if he has enough to complete it?" Luke 14:28

When we share facts with someone else who does not place faith in our story, it has the potential to push them away. If you disagree with my claim, and you tell it to me without consideration for my story, you're going to diminish the trust I have in you. And vice versa. If I disagree with you, if I don't contextualize it with the story behind it, I can push you further away.

For example, someone might tell you that there is no way x, y, or z could happen. But, perhaps I've experienced and studied x, y, and z and so I know it can happen. Your comment now demonstrates your ignorance and my level of trust in you goes down. If instead, you said that I don't believe x, y, and z could happen based on a, b, and c, you still make your claim, but you maintain credibility (when you step back from certainty) and open up the conversation for both people to add more information and expand their stories to more complete ones.

Input >> Processing >> Outputs

When we make our claims, we ought to demonstrate the inputs and processing of why we believe those claims. This helps sustain the trust and provides an opportunity for change. There are no guarantees, but it's at least the possibility of progress.

Share your story, and nest the facts inside. Or, tell their story, and how you reconcile those facts within it. If there is a way to compare, it's going to be through how we and our rival's stories reconcile the realities they are faced with. If someone says something we disagree with, don't just simply say the opposite or throw competing facts at them. Instead, contend with the central issue and lay out the story and reasons you see it differently. Share your story of how you got to a differing conclusion.

And at the end of the day, it's only the real-life effects that may stir change. Since our way of life, the way we live in reality is an extension of our story, reality also serves as a test to our story. And often it's not until certain crises that it's brought to the limit or beyond its limits. In his book, One True Life: The Stoics and Early Christians as Rival Traditions, C. Kavin Rowe explains what this moment looks like.

“…a second-century Roman discovers that Christians will care for the sick and dying in the midst of the plague while Galen [a Roman doctor] and his troupe flee from the ravages of death to their villas in the hills. In this case, Christian nursing practice could begin in a crisis. Following this discovery, however rational investigation would disclose the inadequacies of the Roman’s home tradition that could not be remedied with the resources endemic to that tradition. …the Roman would then try to learn the Christian tradition… and would thereby discover new resources for the inadequacies that surfaced during the crisis. The subsequent narrative provided by the Christian tradition would then make sense of both the reasonableness of his former traditions belief about sickness and death and its inadequacy in the face of Christian care for the dying during the plague.”

The idea with conversation is that we can simulate these types of scenarios so that we can learn and grow before we face the crisis. But for people, most of the time, it's likely going to require a real crisis before they will contend with these issues. But, while this may be what happens later on, we do have the opportunity now to plant seeds for those future moments and to receive seeds from others.

If we recognize that it may not be until the crisis, when we live out our story in that crisis, that the opportunity to change will come about, it can help us to contextualize events so we can proactively act now, and know how we can effectively respond when things come our way. It is a high bar to set for affecting change and for many, it may cause despair. But ultimately, what emotions and feelings the realization causes are based on our core story.

And as our stories diverge and as we go deeper into our respective stories, the gulf between us in society grows larger. And it can be daunting to have such a large chasm of education to simply provide the foundational layers to even have a discussion. But, it's something we must do if we're to talk with those who are so different than us.

Planting Seeds For Later: Crisis & Contradiction Provide Opportunities To Change

When we reach unknown zones and trek through crises, we're often more open to change and opportunity. Sometimes we may plant seeds with those we love and care about, but often it's not until a personal, family, community, societal, or global crisis that those seeds have a chance to grow or if they have grown, to be seen as sprouting out.

The nice thing about talking at the story level is that we spend less time fighting because we know what will make a difference and what won't. And we don't waste time on what won't. And that preserves the relationship and builds trust. Ideally, it fosters curiosity.

This can certainly be challenging when the story people tell affects us, directly or indirectly. When authority figures have drastically differing stories, that can cause us or those we care about harm, it's scary. In these cases, we are inclined to take control and assert power to change things.

For us to properly integrate that controlling impulse will require that we live out our stories in the realm of responsibility we operate and also to trust something or someone greater than ourselves.

For me, that trust is in God, to fill the gaps that come. When things are out of control, I have to trust the outcomes to God. It's beyond me, but it's not beyond him. That is a story I tell myself and I also believe it is a true story, nested in my core story which Karl Barth powerfully conveys in the following quote from 1935, in speaking about the Christians following along with Hitler and the Nazis.

"Let me emphasize only one fact. Christ believed He could not bring real and genuine help to man except by dying for Him."

Every aspect of my life is derived from that story's starting point. And it's a story that continually transforms how I operate in the world and the stories that inform it.

Additional Resources

- Created on .

- Last updated on .